Susan Polgar Memoir 'Rebel Queen' Recounts Struggles With Sexism, Antisemitism, Cold War

Not many chess careers are as long, as varied, and as successful as GM Susan Polgar has crafted. Not only was she the first woman to become a grandmaster via norms, the eldest of the famed Polgar sisters later became an Olympiad gold medalist, a women's world champion, a member of the World Chess Hall of Fame, and a preeminent college chess coach.

It wasn't always easy for her. Her new memoir, Rebel Queen, chronicles her journey from Hungary to the U.S.A. and the challenges she faced along the way. From being denied participation in tournaments she qualified for, to the random travel restrictions of her communist homeland, life was not easy as a young chess-playing girl behind the Iron Curtain in the 1970s and 1980s. She also discussed repeated instances of misogyny, antisemitism, and at one point, an overt sexual assault. The book also has many highlights, including impromptu blitz games versus GM Mikhail Tal, how she helped GM Bobby Fischer come to Budapest, and the quirky pair of incidents that led to her meeting her future husband.

We caught up with Polgar in the midst of her book tour.

Chess.com: Chess.com is excited to be here with grandmaster Susan Polgar, who has just written her memoir, the long-awaited Rebel Queen. Susan, thanks for joining. I would like to first ask you, what inspired you to write your memoir now?

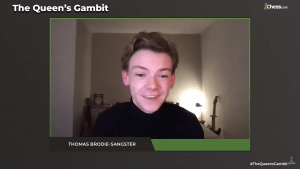

Polgar: Hi Mike, it's lovely to join you. Well, what happened was, as you know, [The] Queen's Gambit, not the opening, but the Netflix series, came out in 2019, and it kind of created a chess boom. And around those days, I got plenty of interview requests, a lot of mainstream media asking whether the series was made based on my life story, with the obvious parallel that I was a pioneer in playing against men and succeeding, and eventually becoming the first woman to earn the men's grandmaster title.

So obviously I told them that the Netflix series was based on a fictional character and not on me, but you know, obviously there were similarities. And at the same time, you know, I had many friends, including in Hollywood, who were suggesting that indeed, a movie should be made of my life story because it's a fascinating story and it's a real story, unlike Beth Harmon's fictional story.

So we started exploring ideas on how to go about it. And one thing I learned even decades earlier, when I was in Hollywood and talking to various studios about the potential of making my life story a movie, was that if I wanted to have any kind of control over the narrative of what would be told in the movie, I should have my memoirs written. And that's when, about three years ago, I started working on it, and as a result, Rebel Queen.

Chess.com: And it's a fascinating memoir. I learned a lot about your life because I've only known you as an adult. So I encourage everyone to read it, but we'll get into some of the struggles of being a female—that's a large part of the first half of the book. But let me just ask you, has your memoir been optioned? Is there a chance that we will see a movie about this book one day?

Polgar: Not yet. The book just came out, like less than two weeks ago, so I'm optimistic that there will be interest, but knowing how the film industry works, its wheels are turning rather slowly, so I'm not sure when it will happen.

Chess.com: Well, we hope to see it one day. Now, in the very early part of the book, of course, it's well known that your father, Laszlo, raised you and your two sisters as a sort of experiment, but it almost seems like that maybe wasn't his master plan until you got really good at chess. Do you think he had the master plan before you got good at chess, or was it only after you started being successful that he hatched this plan?

Polgar: Oh no, he had the master plan even before he met my mother. And he just didn't know that the subject would be chess, which kind of became coincidental when one day shortly before my fourth birthday, I accidentally discovered a chess set and the chess pieces, which I described in detail in the book. And then he was very pleased that I showed interest in chess. It's something he knew a little bit about and he liked. And also, he felt it was the fairest of all games. It's easily measurable relative to sciences or arts when results are a lot more subjective or even longer-term to see the progress.

Chess.com: And we're happy you chose chess over math, although there have been a lot of great Hungarian mathematicians. I think our world is much richer for it. Early on in the book, you talked about your qualification and your ultimate inability to play in the Budapest Championship at the age of five because you were a girl. It seemed to be really emotional for you. Does that experience still drive you today, even though it happened so many years ago?

Polgar: Yes, absolutely, and that was the first of many similar experiences. Obviously, since it was the first, it was very, very painful. And as my dad reminded me as I was writing the book, that I just couldn't be consoled all the way home from the tournament venue. I just couldn't understand why. Why are girls being treated differently in chess than boys? Hence the title of my book, Rebel Queen, because I didn't give up, I didn't give in to the pressure from the chess authorities to play mostly or only against girls and women.

And it was kind of a brave thing to do back then in Hungary, you know, not to do as being told by the authorities. There could be consequences, and there were consequences. Certainly, my life could have been simpler or easier or more comfortable had I just played against women, as I was instructed to do by the chess federation. But at the same time, I don't believe I would have gotten as far as I did, and perhaps neither would have Judit and Sophia.

Chess.com: Now, I know this about you, but many readers might be surprised to learn how fluent you are in so many languages. And even at the young age of five or so, you were already basically fluent in German and Russian and, of course, Hungarian. And then you picked up English so quickly in your first trip to New York. Why do you think you have such an aptitude for language?

Polgar: Well, my mother is a language teacher. She was born on the other side of the Hungarian border in the former Soviet Union, today's Ukraine. So she grew up herself in a multicultural, multinational place where everybody spoke Hungarian, Russian, and Ukrainian to start with. And she always had this aptitude for languages. And I guess she gave me that, maybe even in my genes, but definitely in her actions. She gave me her passion for languages.

She taught me Russian and German early on. And it was kind of funny that my father used to tell her that if you would forget— because obviously it was more natural for all of us to speak in Hungarian, especially when my Russian was just at a very basic level— that you need to wear like a sign on your neck, you know, like a necklace, that reminder to speak Russian, you know, with Susan so she gets to learn.

But on a more serious note, my parents put me in a Russian-language kindergarten where I was the only Hungarian girl in Budapest. It was a kindergarten for the kids of the people who used to work at the Soviet embassy in Budapest. And basically, I knew a little bit that my mom taught me. But then once I was at the age, I don't know, around three, four, I was thrown into that environment. I was just observing and immersing in the language and the culture. And I'm very thankful for it because obviously at that age it's just super easy to pick things up, especially things like languages.

Chess.com: And I know you told me you speak something like eight languages, you can correct me, but one of the ones I did not know was Esperanto. They have such a small, close-knit community. Do you think you're the world's highest-rated Esperanto speaker?

Polgar: Probably I am, although I have to say I have not spoken the language in a number of years. I still understand pretty much everything. I think I would need a few days to be back fluent in it. But actually, I have a lot of very pleasant memories tied to it, including my first international chess tournament. Back in the late 70s, early 80s, in Eastern Europe at least, it was very popular and there were numerous Esperantist chess tournaments. So, actually, it has a really close connection to my chess as well.

Chess.com: This might be the only very chess-specific question I ask you today, but when you were six, you spoke of a teacher coming to your house and focusing a lot on endgames. As you know, many people today love studying opening theory because you can play like Magnus Carlsen for 20 moves. How much does that drive your teaching later in life? Do you still focus a lot on endgames when you were, let's say, a coach at Texas Tech and Webster?

Polgar: Absolutely, I think endgames are a very crucial part of the game for many reasons. By the time you get to the endgame, usually you have very little time left, even in classical chess. So you better know what you're doing. Also, it can be very painful that a well-played game and victory almost in your hand can be spoiled if you don't understand the nuances of endgames.

Also I realized quite early on that unlike openings that constantly change—it obviously changed tremendously in my lifetime as new ideas came about, as engines became stronger and stronger, even today there are constantly new ideas—on the other hand, endgame is something more constant and something in that sense, energy better spent in a way.

That's something you learn, I mean, let's say on a very basic level, how you should checkmate with king and queen against king, it's not gonna change, hasn't changed in 100 years, and will not change the next 100 years either. So I also really appreciated the fact that endgames are kind of more concrete, more understandable, and have fewer unknowns about them. So I really enjoyed the delicacies of endgames.

Chess.com: That makes sense. Now, probably the most graphic story of your entire book, you talked about an attempted sexual assault when you played in Yugoslavia, and it caused you anxiety from being alone for years to come. I'm wondering how you overcame this anxiety? And more specifically, you coached and mentored college women at several universities. What did you tell them about your experiences? Or did you even mention it at all?

Polgar: Yeah, it's a very painful experience to think back on, and I debated quite a bit before I wrote it in the book. But I felt it's important for other girls to know and to be careful. And I'm also hoping that, you know, that today's generation and the next generation of men will learn from it and understand that they can and eventually will be exposed, and that's not the way to treat women.

It was hard to overcome because on one hand, my parents were very protective and they were warning me that, unfortunately, there are some bad people in the world. And as a girl, you have to be even more careful, and that only kind of reinforced that. I hate that they were right. And I was even trying to hide it from them or downplay it to my parents because I didn't want them to feel like "We told you so!" and you know then they would be even more protective and stricter in that sense.

Yeah, I think it took time. It took time, obviously, to trust more again and, you know, when I talk to young girls, I tell them that, "Yes, most people are nice and trustworthy, and you can treat them as such, but be alert because unfortunately there are always bad actors." And as we learned even today, there are sexual assaults that unfortunately women, including in our chess community, have to endure.

Chess.com: It's an important subject. And another important one: You talked about how your wins were being celebrated early on in the West, specifically in the U.K., but not in communist Hungary. And I'm wondering how much of this do you think had to do with you being a girl, and how much was it your Jewish heritage? I know you said your grandmother was a Holocaust survivor.

Polgar: I think it was a combination of various things. There have been comments throughout my career back in Hungary when, while openly anti-Semitism was not allowed by the communist government, at the same time there were many occasions when we overheard or heard from other friends that we were referred to as "not real Hungarians," with a clear hint of our Jewish heritage.

I think the key issue really, with our struggle and my fights with the chess federation and chess authorities, that I refused to play in the women-only competitions for the most part. Because we believed that girls and women are just as capable as men. However, in order to get there, the girls, in my case myself, have to train and compete in circumstances similar to those of the guys. So if the guys train, say, six to eight hours a day and play the best competition they can get, I cannot train only two, three hours a day and play only against lower-rated players.

And back in those days, not doing what you're being told by the government or the chess federation was not something people would dare to do. And so I became a rebel, and I think that's what caused a lot of difficulties.

And so it was a combination of things. But it was also, I think, a little bit of their own personal interests, I mean, the leadership of the chess federation. Because they had such power as being the leaders, they were often given the opportunity to take advantage of it and be the, let's say, leader of delegation and travel with the athletes—chess players in my case—abroad, especially to the West, used to be a huge privilege back in the communist times, the Cold War era.

And also my parents, being protective as most conservative families would be, they said there is no way they're gonna let their 12, 14-year-old daughter travel alone with a male federation official. And they insisted that one of my parents would travel with me instead. And obviously, it was a personal conflict of interest for those federation officials. Therefore, they wanted to get back to me any way they could.

And also the fact that they wanted quick and immediate titles that they can brag about, such as winning this girl's championship or that women's title, versus looking at a longer term, which we were looking at, trying to become a grandmaster, a top player. And they felt, well, we don't have time to wait for that. That may take 10 years. And so that was kind of the primary cause of the conflict.

Chess.com: Well, before we let potential readers know, there are some very joyous and humorous moments in the book, too! Let's talk about one of them. At 13, you traveled to Moscow and you played about six blitz games with Tal. I'll just say that again, you played blitz with Tal in Moscow. I know you've done a lot in your life. I think you just got done playing tennis with Monica Seles, but please tell me blitz with Tal was a top-five career highlight?

Polgar: It was definitely amazing. And it really inspired me for the rest of my life, later on, when I became a champion myself and I wanted to give back to the next generation. I always remember that story, how Tal, who was in the middle of his game in Moscow against [Rafael] Vaganian. At the time, he was a heavy smoker, and it was still allowed in buildings and even at chess tournaments.

So during his games, he would walk up and down in the hallway smoking, and my mother had the courage to go up to him and ask him if he would be willing to play with me. And I couldn't believe that literally within half an hour he was done with his game. He offered a draw, which got accepted, and we were playing blitz.

And moreover, the first game, I'll never forget, he played the Philidor, which was obviously an offbeat opening, maybe not with the best of reputations. But he wanted to get me off my book, I assume. And it was a very fascinating game. I was attacking Mikhail Tal, sacrificing pieces left and right, you know, it seemed unreal. Unfortunately, the attack was only sufficient for a perpetual check, and the game ended in a draw. Nevertheless, obviously, it was one of my favorite memories of my chess career.

[Ed: This video below shows the amazing moment when Susan Polgar played Mikhail Tal, and although that game might be lost to history, the video also breaks down their over-the-board encounter 10 years later.]

Chess.com: That's great. And another really funny story is how you would come to meet your future husband for the first time. I believe you were both playing in a tournament in Vegas, and you both had different opponents do the same things against you, and you bonded over this sort of lack of sportsmanship. Can you retell what exactly happened to both you and Paul Truong in separate incidents?

Polgar: Well, actually it was in the New York Open, 1986, and I was playing Walter Browne, and Walter has been a six-time U.S. champion, and eventually we became very friendly, but at that moment he didn't appreciate the fact that I outplayed him. And probably he'd never lost to a woman before, and did not take it well. And he just smashed the pieces off the board. [Ed: Check out the game below, especially the fantastic finishing move.]

And coincidentally, in that same tournament, Paul's opponent, when he played Bent Larsen, who is obviously a legendary world-class player as well, Paul managed to beat him, and he was obviously the underdog, much lower rated than Bent Larsen, who had a similar response. And it's something that rarely happens, I think it happened less than a handful of times in my life, but it was kind of unusual that it happened around the same time.

That's when we (Susan and Paul) kind of became friends, although then for many years our lives went in very different directions, living on different continents, until we much, much later reunited, kind of as a "Hallmark Story" and ended up together.

Chess.com: That's great. Now, there was a lot of course misogyny by the Hungarian government and also the federation. And you talked about a very interesting meeting where your family sat down and you discussed, like chess players, the pros and cons of defecting. What ultimately led you to decide not to defect and to stay in Hungary?

Polgar: Yes, indeed, throughout the mid-1980s, that was a common discussion, whether we should leave, whether we should stay, whether we should leave, whether we should stay. And ultimately, we felt that my grandparents were still alive. We heard so many stories of people who did defect, and then their families got punished. They were not able to see each other again. And we couldn't have known that the Berlin Wall would fall several years later, and it would not be a problem to go back and forth between Hungary and wherever else in the West we would have chosen to stay.

So we just couldn't do it to my grandparents, and even to some degree to the larger Jewish community, that we were perhaps the most famous Jewish family back then in Hungary. As it is, that there were these "real Hungarians and not real Hungarians" kind of attitude to some degree. And we didn't want, obviously, most importantly, our own families, but even to the larger community to be told, "You see, the Jews are not trustworthy. You know, they got their career started and learned in Hungary and then they benefit from it elsewhere, you know." And that's why I really stayed. And even when I left many years later, it wasn't because I left Hungary, it was because I met my first husband, and I left because I got married in New York, not because I wanted to leave Hungary.

Chess.com: Now, in the late 80s and early 90s, you were consumed by the race to become the first female full grandmaster by the norms-based achievement. And I think you made one comment that Judit was also in the quest for the GM title, and she was supportive of you. I'm just wondering, behind closed doors, were all the sisters really supportive, or was it a little bit more competitive behind closed doors for who could achieve the best results?

Polgar: Well, I think in those days it wasn't very competitive because I'm seven years older than Judit, so it was kind of normal that I would become a GM first. In fact, it was quite an amazing and probably one of the family highlights when Judit, about a year later, a little less than a year after I became a GM, she also managed to make her final GM norm and become Hungarian champion.

And I really felt, not just as her sister, but also as her coach of many years, that it's a vindication for all the sacrifices our family, my father, my mother, and I had to go through long before Judit was even born or started to play chess. I was told countless times that "women just cannot become a grandmaster, it's impossible, it's just physically the women's brain is different from men's and that prevents us from being as good in chess as men."

Yes, not only can we become grandmasters, but Judit also became the Hungarian champion, and Hungary was at that time maybe the second-best or third-best country in the world behind the Soviet Union or the Russians, you know. So it was Hungary, a chess country, and that she won—it was really a vindication of everything I fought for and sacrificed for. It went beyond our own rivalry, which was unimportant compared to the bigger picture of what I fought for, for girls, for women that come after me, including Judit.

Chess.com: There are about 40 women who got the grandmaster title after you, who have you, Judit, and your family to thank. Now, it's well known that Bobby Fischer visited your house in Budapest in around 1993 after his rematch with [Boris] Spassky. But what I did not know is that you personally played a role in simply getting him to Budapest. Can you tell us a little bit about how you made that happen?

Polgar: Yes, that was quite fascinating that after his match he was kind of in hiding in a little town just across the Hungarian-Yugoslav border. And to my biggest surprise, at one moment when I happened to be in Peru, as I later learned, one of our mutual friends reached out to my family to come to visit. And my parents and my sisters went to visit, and the meeting went well, but he was complaining about how I didn't join them.

So they explained that I'm in South America and I wasn't able to, but when I come back, you know, they'd let me know. And so I came back, this is May 1993, and sure enough, I was just very honored and shocked that the legendary Bobby Fischer wanted to meet me.

Obviously, I grew up hearing all the stories about him, studying his games, you know, a legend. Nobody knew where he was even hiding. So long story short, I drove to Yugoslavia and we hit it off well. He was already fascinated by Fischer Random [Ed: Also known as Chess960 or Freestyle Chess] and we played our very first game in Fischer Random there. Seeing how he was living at the time in this small hotel room, I was just throwing up the idea that "Why don't you move to Budapest, you know, you'd have a lot more things to do, we have plenty of nice restaurants, cinemas, spas, you know, I would be happy to help you around? Especially in the beginning, you may have other friends like Pal Benko or Lajos Portisch."

And obviously he was very intrigued and liked the idea, and he asked, "Do you think I could?" And obviously implying that he was going against the U.S. government, and Interpol was perhaps looking for him. So when I was driving back from that first visit to Yugoslavia, meeting him, on the border, I asked the border control guy, "What would happen if I would have a gentleman by the name Robert James Fisher sitting with me in the car?" And he looked at me, not really understanding the question, "What would there be? Does he have a valid passport?" I said, "Yes, he does." "Well, then what would be? He would go across the border with you. Nothing would happen."

So basically, I sent a message to our mutual friend, and two weeks later, Bobby packed up and moved to Budapest along with his bodyguard and Eugene Torre, who had been his companion for some time back in those days. And he actually stayed in Budapest for around eight years.

And indeed, in those early weeks and months, I saw him nearly every day, showed him around. We had countless dinners. And along those ways, those dinners and conversations, we discussed in great detail and experimented with Fischer Random, which eventually turned out to be Chess960. And I helped him finalize the rules, in fact, which initially were quite different from what people play today, in that first only the eight pawns would be on the board. And then the mandatory first eight moves of the game would be to set all the pieces up one by one, not necessarily symmetrically.

And basically only after that, the game, the moves, as we know them in traditional chess, would start. And so we played many games and debated, discussed, you know, should there be bishops on opposite colors squares starting, should castling be allowed, and long story short, after many games we concluded that maybe it would be more harmony to the game to maintain as much as possible of the rules of traditional chess.

And then he reached out to mathematicians trying to find out how many starting positions would there be possible if we restrict the starting positions to having bishops on opposite color squares as starting positions, the kings in between the rooks, as well, and maintaining the rights to castle, as well as making sure the pieces are set up symmetrically as well. So, as we learned at the time, it turned out to be that there are still 960 different starting positions possible. And since the whole purpose of trying to create this chess variant was to eliminate the opening theories that have been developed, even by the early 90s to his opinion, far too much and taking away too much of the essence of chess, as of two intellectuals trying to outsmart each other or out-strategize each other, he was happy and content that there is no way any human can analyze all 960 starting positions, let alone remember those analyses.

And hence the result and the name Chess960. And I'm personally very happy that today there are very significant efforts and tournaments being played with exactly the rules that Bobby and I settled on back in around 1993-94. I think it's definitely a great alternative to traditional chess as we know it.

Chess.com: Fascinating history, and the idea of placing your pieces down is so creative. You might be giving Jan Buettner some ideas. So anyway, that's one step at a time. Now I apologize, but we're gonna fast forward through a lot of your major accomplishments. You became women's world champion in the 1990s. You opened up your own chess center in Queens (New York City), and you became the preeminent college chess coach at Texas Tech and Webster, winning dozens of titles. You started the Susan Polgar National Girls Invitational. You won a silver medal with the U.S.A. Women's Team. I could go on and on. Is there anything that you did not accomplish in your chess career that you wish you had?

Polgar: Well, obviously, I wish I had become a top-10 player. If I didn't have all those obstacles to overcome constantly, I may have gotten further than I did. But I'm really, really proud that my sister did become a top-10 player, and I have the Susan Polgar Foundation, that's a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. I still have a lot of dreams to accomplish when it comes to women's chess. I'm hoping one day to find a benefactor who would support the dream that many more women can become top players and perhaps even a woman to become a world champion.

Chess.com: That will be great to see. Now, let me ask you, we've talked about the idea for a while of getting all 42 female grandmasters to play an event. But there's a problem, we can't get your sister to play. So do you have any pull with Judit? Is there any way we can get her to play any sort of competitive format?

Polgar: Well, I don't know. The good news is that all 42 women who hold the grandmaster title today, or ever earned it, are still here, we're still alive. So that's the good news. And I think we have to hurry up. Some people are getting up in age. You never know. You never know if there may be some kind of format. Maybe we can all 42 give a simul, for example, to young girls. That could be a format to promote just for girls.

Chess.com: O.K., and Judit, if you're listening, I'm sorry to put you on the spot. Susan and Judit both became great ambassadors even in their non-competitive days. So we thank you for staying in the chess world. Let me just ask you one question to get you out of here. In the opening pages of the book, there was a really funny story. You said you basically learned recently that your father learned how to play chess originally to impress women. I hope I have that right. Did the process of writing this memoir bring you closer as a family, and did you have a lot of discussions that you may not have had if you were not writing a book?

Polgar: Yes, indeed. That was one of the interesting discoveries I came across while writing the book. I asked my dad, "How did you actually discover chess yourself?" And he was telling me that in his freshman year in high school, one of the very first days of high school, they had a chess club. And one of the members of the chess club, a good-looking girl, came up to him and told him that we have a chess team and we need a fourth. We only have three guys on the team so far. And he said, "I'd love to!" because of the girl who asked, but "I don't even know how the pieces move," And she says, "Don't worry, we'll teach you." And indeed so they did.

So he joined the chess team. And of course, as expected, he lost practically all his games until the very last one, that first year of high school. But then, eventually, he wanted to impress, I think, this girl. And I don't think they ever really dated. But it kind of ignited his interest in chess. He got really interested. And he learned. But he never really competed beyond high school. He only rediscovered chess when I showed interest in it a number of years later. And then he discovered that chess books exist, and he started learning with me, and, of course, for a while, he was a few steps ahead of me.

Chess.com: And speaking of chess books, chess fans have a new one to enjoy, Rebel Queen. I enjoyed reading it and there are so many more anecdotes and stories about how Susan overcame the misogyny, antisemitism, and communist travel restrictions. There's so much to read about. We only touched the surface here today. So it's been great talking with you, Susan, and good luck on your book tour.

Polgar: Thank you so much, pleasure joining you.

You can learn more about the Susan Polgar Foundation on their website and buy her book Rebel Queen on Amazon.