Kasparov, The King's Gambit and Opening Theory Before Castling

In my last blog post, I wrote about lost traces of medieval chess opening theory. My conclusion was that there's virtually nothing left of chess opening "theory" from the Middle Ages and that the introduction of the new bishop and queen's moves changed everything.

But even after these historical change of rules, which started in Spain around the end of the 15 century (probably between 1475 and 1485), chess still wasn't the same as it's being played today.

Several features, such as the en passant capture and, especially, castling, were still 'under construction' and in fact wouldn't be universally recognized for several centuries to come. This sheds an interesting light on some of the openings we still play today.

I will illustrate that by showing some concrete examples from the most romantic of all openings, the King's Gambit, and will try to convince you that the legacy of the old masters continues to influence today's top players - including Garry Kasparov.

Even though we can study the phenomenon of 'modern chess opening theory' from the original sources from the beginning of the 16th century onwards, it would be a mistake to equate the theory described in these works with our own opening theory. Here's a simple example from a line first introduced by the famous Spanish priest Ruy López de Segura, who lived from c. 1540 until c.1580 and who is now mostly associated with the 'Spanish (or Ruy Lopez) Opening' (which he actually didn't invent):

Any modern-day fan of the King's Gambit knows that 2...Bc5 is an annoying little move preventing an early castling for White. It's no surprise, therefore, that opening theory from the 17th century onwards has largely evolved around variations involving an early c2-c3 and d2-d4, trying to block the bishop and achieve castling after all.

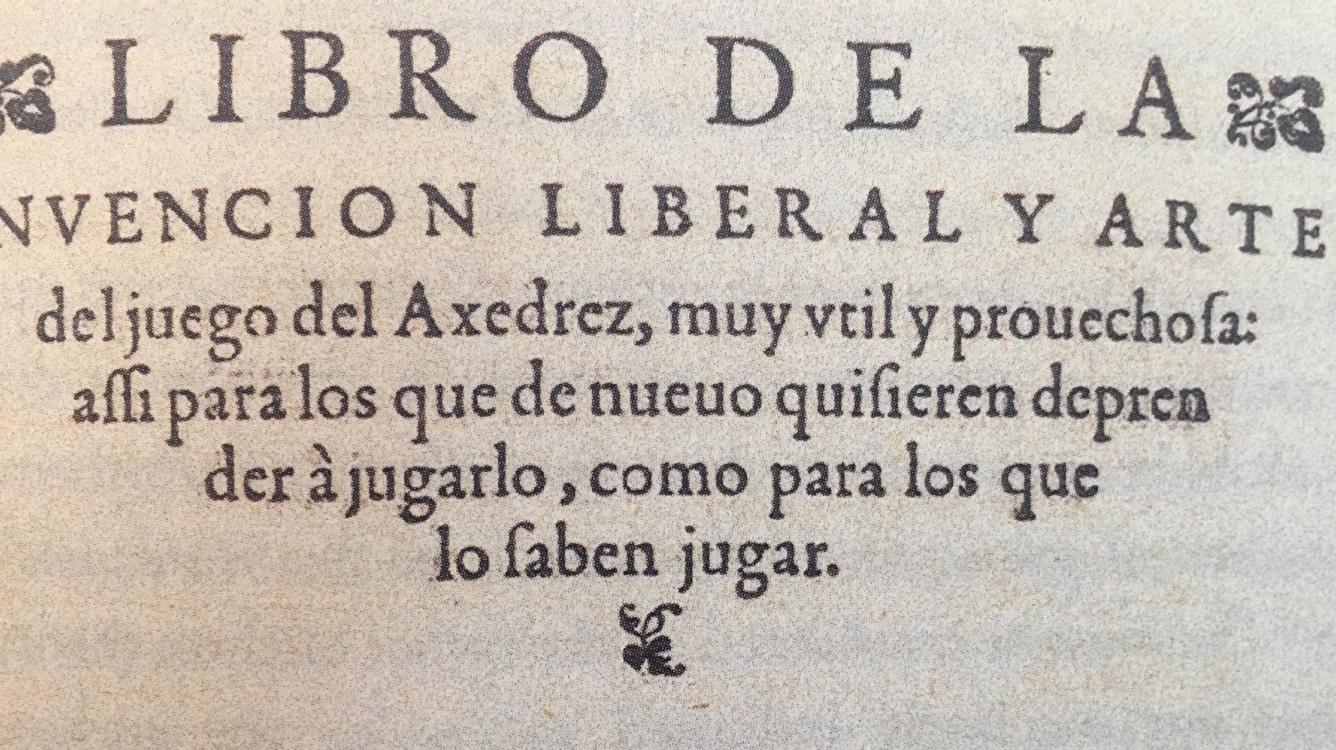

But here's the interesting thing: Ruy López introduced the move 2...Bc5 at a time when castling was not yet generally accepted. Moreover, he didn't accept castling himself! We know this because in his highly influential book Libro de la invencion liberal y arte del juego del Ajedrez, published in 1561, Ruy Lopez describes the rules of chess according to local varieties that were practised at that time. In Spain, castling was not common practice yet. Instead, chess players still employed the ancient (in fact, medieval) king's leap.

The king's leap can be traced back to the 13th century, where it appears in the famous Alfonso X Manuscript (1283) from Spain (Castille) and the Italian (Lombardy) Cessolis Manuscript (dated between 1275-1300).

Two pages from the Alfonso X Manuscript (1283)

Essentially, the old rules allowed the king to 'jump' three squares in each direction (not only from e1 to g1 but also from e1 to c3 or from e1 to g2). Sometimes, the king was also allowed to 'jump over' other pieces.

With the introduction of the new chess rules at the end of the 15th century, allowing the bishop and the queen to extend their reach dramatically, the leap to the third rank became less and less popular, as it exposed the king too much. But leaps to the second and first rank were still common at the time the first books on modern chess were written. Here's an example from the Göttingen Manuscript (Spain, c. 1500-1510):

1.c4 c5 2.Nc3 e6 3.e4 Nc6 4.f4 d6 5.Nf3 Bd7 6.d3 Rc8 7.Be2 Kc7

Play now continued 8.Rf1 Kb8 9.Kg1 (as you can see, White already employs a kind of 'artificial castling' albeit with the rook being played first!).

Here's another example from the same source:

Here Black played the move 10...Kg8, jumping over the bishop. (Quoted from J. Garzón, The Return of Francesch Vicent (2005), about which I've written before. According to its author, this "clearly proves that originally the leap has nothing to do with castling.")

As can be sensed from the above examples, tracing back the precise evolutionary steps which lead from the king's leap to castling is something that's easier said than done. Whole studies have been devoted to this topic. The Dutchman Peter J. Monté, in his book The Classical Era of Modern Chess (2014), has done an amazing job sorting all available evidence from the original sources and presenting it in a coherent fashion. (I have taken many of the examples in this blogpost from his book.)

Back to Ruy López. In his above-mentioned treatise, he describes the differences between the Spanish and Italian local rules. First, he mentions the Spanish king's leap:

"The freedom to go three squares on the first move, as he likes as a pawn or a knight or a rook or a bishop or a queen in order to advance (...). This is the freedom he is entitled to, being the king." (translations here and elsewhere by Monté).

"Note that in some parts of Italy it is usual to leap the King for his first move through the whole line from his own square to the extreme one of the Rook, and to join the Rook to it, combining the leap all in the one move; and in other parts no more than three squares, from his own to his Knight's square, and on the Queen's side from his own to the Bishop's square and joining one of the Rooks to the King all in one move."

"The XI [Rule] says that two moves in one turn are not allowed, for instance, when playing the rook next to the king and leaping all in one turn... as is usual in Italy; such a thing should be forbidden."

Ruy López on a post stamp

There's much more to be said about this (see Monté's excellent book if you're interested), but for now, let's pause and note that Ruy López, whom we all know for having made such important contributions to modern chess opening theory, actually didn't approve of castling. This means we should view some of his variations in a different light altogether.

We now know enough of the background to go back to the 2...Bc5 line in the King's Gambit.

So why did Ruy López analyze this move at all, if it didn't prevent castling as it does today? Monté writes the following about it:

"Although the move did not hamper White's castling as it does nowadays, it discouraged him from playing Rf1 and leaping with the king as well. Moreover, it suits López' principle of the bishop's free development and his preoccupation with the consequences of the advanced f-pawn (in this case an attempt to save the important center square d4 for Black). Far from being a confusing alteration, but rather an illustration mark of honor, one may name it henceforth López Defense."

Apart from Monté's (in my opinion, justified) point that the move ...Bc5 should really be named after its inventor, this fragment shows that some opening ideas, which we automatically assume to have been coined with a certain purpose in mind (such as, preventing castling) were originally played for different reasons.

Consider the King's Gambit in general. These days, we associate this romantic opening with quick development, early castling and, if possible, a swift and dazzling sacrificial attack against the Black king. In fact, Garry Kasparov seems to echo this sentiment when, in My Great Predecessors I (2003) he describes the style of the 16th and 17th players as follows:

(...) Never missing a chance to give check, bring the queen immediately into play and, not thinking about the development of all the pieces, launch[ing] a dashing attack on the king. The combination either succeeds, or suddenly turns out to be completely incorrect. The level of defense is terrible and there is a complete lack of absence of any deep plan."

Whilst Kasparov is not wrong in his general assessment (and as I will argue below, he actually thinks more nuanced about the approach in practice!) , the Lopez Defence proves that already in the mid-1550's, there was definitely an emerging view as to how to develop pieces centrally, and how to hinder attacking chances of the opponent.

In fact, when we're talking about the King's Gambit specifically, we shouldn't forget that this opening was already analyzed when castling wasn't allowed yet (not even in Italy). Its original purpose was, first and foremost, to fight for the center. There's another curious variation which illustrates this.

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.d4 A principled move, but it allows 3...Qh4+

This check is usually met by 4.Ke2 (or, less attractive, 4.Kd2), moves which were in fact analyzed as early as 1617 by Pietro Carrera. However, there used to be a third way of playing this gambit:

4.g3 fxg3 5.Kg2

Now that's a cool king's leap! This line was called the Guspatera - 'guzpátaro' means 'hole' in modern Spanish, and according to Monté "the nickname is probably alluding to g2, offering a hole for the king's leap".

The line appears in the somewhat mysterious Leon Manuscript, previously attributed to the Italian Giulio Cesare Polerio (c. 1548-c. 1612) but (according to Monté) the work of an anonymous contemporary copyist, written around 1581. The quoted 'game' may have been played in an alledged match between Spanish and Italian players in Madrid in 1574 or 1575.

Play continued 5...Qxe4+ 6.Nf3 gxh2 7.Rxh2 d5 8.Nc3 etc. White has some play for the sacrificed pawns. (It strongly reminds me of a crazy gambit called 'The Fred', which starts with the moves 1.e4 f5 2.exf5 Kf7??! 3.Qh5+ g6 4.fxg6 Kg7).

It's interesting that the Leon Manuscript also analyzes the King's Gambit from the Italian perspective, where castling was already allowed. The famous Muzio Gambit, symbol of the romantic style of attacking, is introduced for the first time in history:

But it would be too simple to assume this is the beginning of analyzing openings in general, and the King's Gambit in particular, with 'modern day' castling (then known as a la Calabrista), no questions asked. Another Italian, Gioachino Greco, nicknamed Il Calabrese (1600-1634), analyzed the same move sequence, but... used a different kind of castling (a la Napolitana). This led him to analyze the same variation, but with the white king on h1!

This is clearly an even better version for White, as in some lines he doesn't have to be bothered by a check on d4 from the black queen. (And this still isn't the end of it, since later in the opening's analysis, Black castles by placing his king on h8 and his rook on g8! I won't go into these fascinating details here, but refer the interested reader once more to Peter Monté's book.)

Before moving on to en passant capturing, I want to emphasize that I am heavily simplifying an extremely complex subject here. There are many subtleties to the entire discussion and different sources often disagreed on which rules to follow. I can't resist giving one amusing example from the King's Gambit. Here's a line from Pietro Carrera's Il Gioco de gli scacchi (1617):

1. e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Bc4 Qf6 4.d4 d6 5.Nc3 c6 6.Nf3 g5 7.h4 g4 8.Ng5 Nh6

Here Carrera continues with 9.Rf1 Qe7 10.Bxf4 which is actually fine for White according to modern engines. However, in his 1634 treatise, the move 9.Rf1 was called a big mistake ("errore grande") by Alessandro Salvio (1570-1640), another Italian but not following the same rules. Salvio claimed that 9.0-0 was winning!

Firstly, Salvio apparently wasn't aware of the different rules Carrera, who rejected castling as an anomaly, adopted. Secondly, Salvio himself was rather inconsistent when it came to putting casting into practice. (He not only castles by moving the rook to f1 and the king to g1, as in the above example, but also by moving the rook to e1 and the king to g1 - and even by moving the rook to e1 and the king to h1!)

Thirdly - and most interestingly from a modern point of view - it's actually debatable whether 9.0-0 is really so much better than 9.Rf1. Stockfish prefers the latter, probably on account of the variation 9...f3! (missed by all authors) with the point 10.gxf3 Qg7 and the pin on the g-file gives Black certain counterchances. Another nice example where castling is not necessarily an advantage in this opening.

After looking at all these examples of various types of king's leaps and casting, we should not ignore changes and local differences in the en passant rule, although this had a lesser impact in practice. The equally complex field of historical research is impossible to summarize here, so let me give just one easy-to-understand example, once again in the King's Gambit, and again from Ruy López' book.

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.e5 Nh5

Quite a well-known position actually (it's called the Schallopp Defense now), which still occurs in high-level tournament practice from time to time (for example in a game Gashimov-Graf, 2005). Ruy López mentions this position in his book, but then he says something quite remarkable and at the same time obvious (to our eyes): 5.g4 doesn't win a piece, commenting that "it is usual in Italy that a pawn can passar battaglia (...)".

The way I understand the (highly hermetic) literature about the subject of historical en passant capturing, the phrase passar battaglia means so much as 'declining the square of capture', implying that the pawn cannot be taken on the square which it passes (in this case, g3). Hence why 5.g4 won a piece in the 'Italian' style. (Amusingly, I found one modern game in the database in which White plays 5.g4, and after 5...fxg3 continues with 6.d4. It's just conceivable that the first player wasn't aware of the en passant rule in modern chess!)

So, we've seen various cases of en passant and castling rules from the early days of modern chess. With all that in mind, I now invite you to look with different eyes at a recent game between two of the greatest names in chess of recent times.

A classic battle! (Even if it was just a blitz game.)

I remember that the commenters in Saint Louis expressed surprise (surely in part on behalf of the audience) that Kasparov, with a king on e2, "had given up the right to castle" so easily, wondering what he had "cooked up". But it's not surprising at all. Kasparov restated a centuries-old principle, namely that the King's Gambit is, first and foremost, an opening where White fights for control in the center - even without the right to castle.

Garry Kasparov plays the King's Gambit vs Sergey Karjakin at the 2017 Saint Louis Rapid & Blitz tournament.

I hope I've shown you that it wasn't only 'recent' World Champions like Kasparov, Fischer and even Steinitz and Morphy, who understood this - but that, in fact, the very first pioneers of modern chess opening theory thought the same. Even without the right to castle, they saw the huge potential of the King's Gambit as a way to fight for dominance on the chess board. Kasparov has merely proven them right once more.

(This article wouldn't have been possible without Peter J. Monté's The Classical Era of Modern Chess, McFarland&Company, Inc., Publishers, 2014.)