Alekhine vs. Euwe | World Chess Championship 1935

I am launching a series of articles about 10 Evergreen World Chess Championships, and I am going to open it with one of the most stunning upsets in the history of World Championship matches, 1935 Alekhine-Euwe.

One of the reasons why I picked it up for the new series is that 1935 World Championship has already been compared to Carlsen-Caruana World Championship. Grandmaster Michał Krasenkow, who commented the 3rd Carlsen-Caruana game for ChessPro.ru, shared the following observation:

The beginning of the match strangely reminded me (and, as it turned out, a few of my colleagues as well) a match that took place 83 years ago, 1935 Alekhine-Euwe. Naturally, the reigning World Champions plays in a style that is completely different from his distant predecessor. He is also free of the "chronic illness of the Russian intelligentsia" [AT: alcoholism], which plagued the 4th World Champion, but otherwise the situation is similar – after many years of domination Carlsen is going through a creative crisis.

His opponent is an extremely pleasant young man, an outstanding player, but – no offense to Fabiano – somehow having neither a unique style of his own nor a special champion's charisma. Perhaps the only World champion whom Caruana reminds in this regard is Euwe. And the first game, in which Magnus outplayed the opponent and then missed the obvious win makes one remember the howlers by Alekhine in that match.

Of course, the history does not always repeat itself, and the scenario of 2018 match is still completely unclear.

Somehow Krasenkow's comparison of Fabiano Caruana with Max Euwe sounds odd, almost condescending, and yet the readers were quick to point out that Caruana probably would not mind following Euwe's footsteps in winning the match and becoming a new World Champion!

Max Euwe did not have to go through the arduous qualification process to secure the right to challenge Alekhine. In those days, the World Champions could freely pick and choose their opponents, and Alekhine's choices were, shall we say, conservative. He played two matches with Efim Bogolyubov, did not grant a rematch to Jose Raul Capablanca, and did not seriously entertain the idea of playing the rising star Salo Flohr. However, in May 1934 Alekhine signed an agreement for the World Championship match against Euwe, that was tentatively scheduled for the autumn of 1935.

By mid-1930s Euwe had a long and well-established track record. He won a "World Amateur Championship" in 1928 (one of the first tournaments to be organized by FIDE) and Hastings 1930/31 (ahead of Capablanca). However, true to his "amateur" status he mostly focused on math and played in the chess tournaments only when it did not clash with his teaching duties. When he did play, Euwe demonstrated good results, finishing second to Alekhine in Bern 1932 and generally scoring against the World Champion.

On the other hand, Euwe rarely finished first in the international tournaments. In Bern 1932 and Zürich 1934 he shared the 2nd place with Salo Flohr, and a few months later he would share the 1st place in 1934/35 Hastings Christmas Congress with Flohr and Sir George Thomas (although ahead of Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik). In short, Euwe's results were solid and consistent, but not exactly breathtaking, which probably explains why Alekhine was comfortable with the idea of playing a World Championship match against him. However, Alekhine was smart enough to include a clause about the return match in case he lost the World Championship!

It is not well-known, but Euwe and Alekhine have already played a match against each other, a training competition in 1926 when Alekhine was preparing for his first World Championship match against Capablanca. It turned out to be a surprisingly close affair – Alekhine was able to snatch the victory only by winning the decisive last game (+3-2=5).

Over the next decade Euwe also played matches with Bogolyubov (twice), Capablanca, Flohr (twice), not to mention the lesser masters. Euwe drew or narrowly lost most of those matches but he obtained almost unprecedented match experience in the process.

The general opinion was that Euwe stood little chance in a match against Alekhine. The World Champions was of the same opinion and sounded almost boastful in his interviews prior to the match.

A rare dissenting voice could be heard in the following clip of Capablanca & Euwe giving a joint interview to a Dutch journalist in 1935:

Capablanca gave an insightful evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the World Champion and Challenger:

Dr. Alekhine's game is 20% bluff. Dr. Euwe's game is clear and straightforward... not so strong as Alekhine's in some respects, but more evenly balanced.

The journalist, Han Hollander, then turned to Euwe and asked the same question: "What do you think about your match vs Alekhine?". Euwe's carefully hedged his bets in the answer:

This is not an easy question to answer, because my thoughts about the chances change all the time. One moment I am very optimistic, the other I am very fearful of match. When I look at it objectively, I have to say Alekhine's tournament results are much better than mine.

Note the word "tournament" – Euwe clearly thought that the match was a different matter! He beat Alekhine in their last game prior to the match (Zürich 1934) and went through a rigorous program of preparation for the World Championship. In a move that was innovative for the time, Euwe's program was not limited to chess but also included an intensive sports component.

The match began in October 1935 in Amsterdam and about half of all games of the match were played in the capital. However, starting from 4th round the players went on the road, and visited 12 more cities over the next two months. This "travelling circus" might sound odd today, but it was not unusual at the time. For example, Alekhine's 1934 match vs Bogolyubov was played in 12 German cities, and the famous 1938 AVRO tournament would also travel all around The Netherlands.

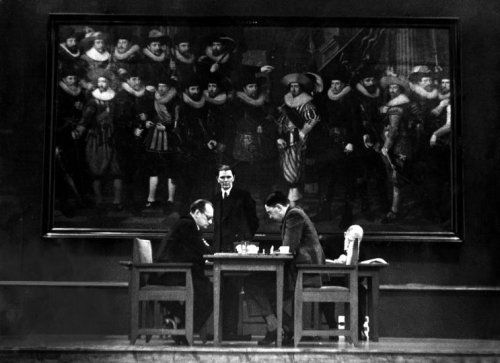

Alekhine and Euwe playing a World Championship game at the Rijksmuseum © National Archives of The Netherlands

Alekhine and Euwe playing a World Championship game at the Rijksmuseum © National Archives of The Netherlands

One of the main reasons behind this arrangement was the need to raise money for the match. Alekhine asked a steep fee for the World Championship match, although he agreed on less amount with Euwe (10,000 Dutch guilders, equivalent to $6,700) than what he demanded from Capablanca ($10,000).

The case of Capablanca was personal for Alekhine. It was the Great Cuban who has fixed this amount in the first place, in so-called "London Rules" that he insisted all potential challengers to sign in 1922. Alekhine was one of the signatories of "London Rules" and had to raise the full amount for his World Championship match in 1927, so he insisted that Capablanca should do the same if he wanted a rematch.

The committee that supported Euwe's bid for the championship went for crowdfunding, with multiple cities contributing to the prize fund in exchange for a chance to host one or more games of the match. It was a tough way to raise money and the budget was tight. In the end Alekhine got paid, but nothing was left for Euwe. The challenger was playing this match only for the glory.

Alekhine started the match on a high note, winning the first game in a brilliant style:

Alekhine lost the next game but responded to the loss with two straight victories. After two draws he struck once again in the 7th game, raising his advantage to 5:2.

A big factor in Alekhine's domination at this stage of the match was Euwe's unfortunate choice of French defense as the main opening against 1.e4. Euwe tried it four times in the match but only scored half a point in these games! Euwe knew the theory, but the resulting positions were unfamiliar to him and suited Alekhine's attacking style perfectly.

However, in the next 7 games Euwe came back from the dead and evened the score in the match! In the stretch from 8th to 14th game Euwe won all of his White games, while losing only once with Black. It should be noted that in this match the first-move advantage played a huge role, with White scoring +13-4=13.

In this phase of the match Euwe's advantage in the openings finally started to tell. He solved his problems with Black pieces by finding the ways to equalize against 1.d4 in Slav and abandoning the French defense in favor of the more solid Open Spanish.

On top of that, Euwe consistently obtained opening advantage with White. This forced Alekhine to jump from one opening to another, without much success. More importantly, it drove Alekhine into a vicious cycle – he tried to solve his opening woes by going for complications, but Euwe calculated very well and was able to refute Alekhine's unsound ideas.

Most of the games were full-bloodied fights and the incessant travel from city to city also took its toll. Fatigue set in early on both players, and never left them until the end of the match. Starting from 10th game, both opponents made numerous errors that sometimes rose to the level of inexplicable blunders.

We will start with two games that were decided in the opening...

This kind of errors led to a somewhat scornful remark by Capablanca in his interview to "New York Times" (11 January 1936):

Without detracting anything from Dr. Euwe or Dr. Alekhine, championship match such as they played cannot possibly bring out what it should – the very finest in chess. Title matches such as this are more a struggle of endurance. I think this reflected in the play. Some of the games were very fine. Others below standard.

Capablanca's commentary should be taken with a pinch of salt, as in 1936 he was actively positioning himself as the most deserving candidate for a World Championship match. However, Euwe informed Capablanca that his bid would have to wait until after Euwe's return match with Alekhine. Capablanca was not happy about it, as it pushed his own prospects for a World Championship match to 1938 at the earliest. As he remarked in the same interview, "I am not getting any younger".

It is through this lens that one should view Capablanca's suggestions for the changes in World Championship rules and regulations:

For a remedy the Cuban suggests limiting a match to 16 or 20 games at the most. Also the games should be played only every other day. The play each day should consist of a four-hour session, a two-hour recess and then another three-hour session, with no analysis allowed at any time. The entire match could be played in a month.

Of course, a format with no analysis of the adjourned games, breaks between playing sessions and rest days between the games would have benefited the aging Capablanca the most.

Alas, 1935 match was the exact opposite of that ideal. It was the first World Championship in which the players were officially allowed to use the help of the seconds (Salo Landau for Alekhine, Hans Kmoch and informally Salo Flohr for Euwe), but at the same time there were no breaks built into the program. Thirty grueling games and no time outs – no wonder that there were so many blunders!

Alekhine, Euwe and Flohr interviewed for the Dutch radio © National Archives of The Netherlands

Alekhine, Euwe and Flohr interviewed for the Dutch radio © National Archives of The Netherlands

After 14 games the match was drawn at 7:7, but then Alekhine won two games over a short span. We have already seen the ending of 16th game; the other victory was a fine positional effort in the 19th game. Going into the last third of the match, Alekhine was leading "+2" and had all reasons to look into the future with optimism.

However, between the 20th and 26th game the match went through a complete turnaround. During this stretch Euwe won 4 games and drew 3, without losing any. This swung the balance from "+2" in favor of Alekhine to "+2" for Euwe, with only 4 games left to go in the match.

We will look at the 20th game, which could serve as a template for the whole match. Alekhine got a difficult position out of the opening, tried to solve his problems with tactics but in the end he was simply outcalculated by Euwe:

During this streak Euwe played his best game of the match, which received a poetical title "The Pearl of Zandvoort" (Zandvoort being the name of the town where the game was played). We will give it with Euwe's own annotations. It has been updated and superseded by later analysts (particularly, Kasparov did a great job dissecting it in "My Great Predecessors") but it seems fitting to give it with the original commentary of the winner:

Alekhine found the strength to win in 27th game, reducing the gap to just one point. He also had chances in 28th and 29th games, but both times Euwe managed to escape with a draw.

Before the last and decisive Game 30 Euwe informed Alekhine that would gladly agree to a draw at any point. Alekhine played a strange mix of Queen's Gambit Accepted with Grünfeld defense and tried to organize an attack on the kingside. However, unlike the 1926 match, Euwe played confidently and by the time of adjournment had two extra pawns in the endgame and a completely dominating position. When Alekhine realized that Euwe was planning to adjourn the game, he finally took Euwe's offer and stood up from the board to proclaim the new World Champion.

Unfortunately, Euwe's victory in 1935 will be forever tainted by the talks of Alekhine's alcohol consumption during the match, most often wildly exaggerated.

Euwe himself weighed in on this matter in the latter years. The following passage is quoted from a brilliant piece "Chess and Alcohol" by Edward Winter:

I don’t think he was drinking more than he usually did. Of course, he could drink as much as he wanted: at his hotel it was all free. The owner of the Carlton Hotel, where he stayed, was a member of the Euwe Committee, but it was a natural courtesy to the illustrious guest that he should not be asked to pay for his drinks. I think it helps to drink a little, but not in the long run. I regretted not having drunk at all during the second match with Alekhine. Actually, Alekhine’s walk was not steady because he did not see well but did not like to wear glasses. So many people thought he was drunk because of the way he walked.’

Euwe went on to say that he believed Alekhine was probably drinking before the 18th game (a draw), certainly before the 21st (which Alekhine lost; we briefly mentioned it in the analysis of 20th game), and before the decisive 30th game (!).

Alekhine's drinking was openly discussed in the Dutch press during the match. However, in other publications this topic was more subdued, or never brought up at all. For example, the only reference to the incident in 21st game in "New York Times" was a brief note with a subtitle "Indisposition of Champion Causes Him to Postpone 22nd game with Euwe." (22 November 1935), which addressed the matter in a very diplomatic tone:

For the first time since the match for the world's chess championship between Dr. Alexandre Alekhine of Paris and Dr. Max Euwe of Amsterdam started early in October there was a postponement today in the schedule, which called for the twenty-second game to be contested tonight at the Monopole Building.

The indisposition which overtook Dr. Alekhine and, many though, caused his defeat in the twenty-first game, was responsible for the interruption. Loath as he was to disrupt the program, the champion decided that a rest from play was imperative and would be to the best interest of all concerned.

Accordingly, he availed himself of the privilege, granted under the rules governing the match, of taking a rest period. This, he hoped, would restore him to normal playing condition.

The following video, which has recently surfaced on YouTube, is a perfect conclusion to the report on 1935 World Championship.

It is a most peculiar piece, which follows the match from the opening speech by an impressively bearded Dutch dignitary to the gala dinner that closed it, with many stops along the way, including a segment in which Alekhine and Euwe pretend to play a game (without chess clocks!) and Alekhine cannot help but smile when seeing a Budapest gambit on the board.

In the traditions of the time the speeches at the closing dinner smoothly transitioned from Dutch to French to German and back, making it a nice test for the modern-day polyglots.

In his speech Alekhine congratulated "a true gentleman champion" in what could be construed as an attempt to compel Euwe to comply with the contract that was signed prior to 1935 match. In response Euwe said that he always considered himself an admirer and a friend of Alekhine, and that he was looking forward to a rematch in two years.

Euwe held true to his promise and indeed played a return match with Alekhine in 1937. That match was quite close in the beginning, but at the mid-point of the match Euwe simply fell apart and ended up losing badly, +4 -10 =1.

This loss led to a certain shift in perception of his crowning achievement in 1935. To this day Euwe is sometimes viewed as an "accidental champion", or as someone who was not on the same level with the other great players of the past.

However, later World Champions seem to disagree. For example, Kasparov quoted Vasily Smyslov's opinion on this matter in "My Great Predecessors":

Nothing accidental happens in life: whatever form Alekhine was in then, a match against him could be won only by a master of the highest class. Euwe played better and he rightly became champion.

Spassky, Kasparov and Kramnik also expressed similar opinions about Euwe.

After the World War and Alekhine's untimely death in 1946 Euwe remained the only World Champion still alive. There were even talks of declaring him a World Champion, but instead Euwe had to join another race for the title. In 1946 Euwe narrowly trailed Botvinnik in what was effectively an informal Candidates Tournament in Groningen, and in 1948 he took part in the World Championship Match tournament. Alas, by then Euwe's best days were behind him. He finished last in 1948 and in the later tournament his age started to play larger and large role. The Candidates tournament in Zurich 1953 is a great case in point – Euwe started really well and was sharing 5th place at the end of first half (15 rounds, equivalent of maybe two tournaments these days!). However, he could not withstand the marathon distance of the tournament. In the second half he did not win a single game and finished the tournament next to last...

Once his playing days were over, Euwe established himself as one of the leading chess writers and educators in the Western world. He published a countless number of books in Dutch, German, English and many other languages, which served several generations of chess players. Euwe also earned an impeccable reputation as a chess theoretician and arbiter.

In 1970 Euwe was elected FIDE President. He served in this capacity for eight years, navigating through the most difficult times, with Spassky-Fischer "match of the century" and Karpov-Fischer "match that never was" both landing during his tenure.

Euwe lived a long life and passed away in 1981. His chess career spanned most of the XX century. Max Euwe played against all World Champions from Emanuel Lasker to Robert James Fischer, but he would be forever remembered as the only person who ever managed to knock Alexander Alekhine from the throne.

Congratulations to @ddtru and @Rocky64 for winning Chess.com's November Blog of the Month contest. Learn more here.