Petteia - Polis & Ludus Latrunculorum, as partially chess ancestors

It was in Yuri Averbach's History of chess [2012], where I've read firstly about a possible influence of ancient Greek board games on the invention or/and development of chess in India. An idea that seems to be supported by him since 1991. It felt really attractive as it could come along with our knowledge on history.

Since the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great during 327-325 BCE, the Greek element was present in the area for centuries. Firstly with the Hellenistic Seleucid empire. But even when it was defeated by the Parthians during 2nd century BCE and shrinked to the western coasts of Near East, the independent Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and then the Indo-Greek one, just North-West of the Indus river, remained dominant in the area. Till the last years of the 1st c. BCE, when the Kushan empire made its appearance and started controlling these regions up to the 4th c. CE. This Indo-Greek interaction can be tracked in the artifacts of the so-called Greco-Buddhist art, mainly appearing in the area of Gandhara. But the Greek element can also be found during the first two centuries of the Kushan rule. Just consider that Kushans, after conquering the area, used Greek language as their official one, eg. on their coins. And this until mid 2nd century CE [generally on Kushans, check Harmatta [ed. 1994]].

But this wasn't the only contact between the people of India and the western world. Cassius Dio, a Greco-Roman statesman and historian of the 2nd-3rd c. CE, wrote [in Hist.Rom, 68.15] that in 107 CE ca, an embassy from India arrived at the court of the Roman emperor Trajan; and archaeological findings comfirm some trade between these people. This embassy probably was of the Kushan empire, as the strongest at the time state placed in the lands of India.

Kushan Empire is one of the candidates for the invention of chess. Josten [2001, and citing Isaac Linder] attracts our attention to some artifacts excavated in the site of Dalverzin Tepe, in the heart of Bactria - now Uzbekistan [fig. 01 & 02]. They are miniatures of animals, an elephant and a bull [?], made by ivory and dated in 2nd c. CE. And by many authors are considered of the first chess pieces.

It has been noted the resemblance between this elephant and similar chess pieces coming from India or Persia. Bull seems a little awkward, but Linder [1975] reminds us of the bull-piece of shatranj al-Kabir, found in one manuscript described in Murray [1913, p. 346]. However, this latter manuscript should be dated surely not earlier than 15th c. Generally without a relevant written record or other artifacts, the identification of these pieces as chess ones is a little obscure. However, if we would choose to place them in the chess history timeline, it can't be easily ignored that these items are coming from a place and time where the Greek element was really intense, if not dominant.

Footnoting: On the Dalverzin Tepe findings. Excavation was concluded in 1972. Of the following writers, Pugachenkova & Turgunov were leading the archaeologists' group. Turgunov [1973] identifies them as chess-pieces and dates them in 2nd c. CE, mainly based on coins found in the same room. It's also tried a comparison with some other artifacts found in Ayrtam's site [Uzbekistan, near Termez] and dated in the same period. The given photo of the latter was really bad. If they are truly chess-pieces, they seem more abstract artistically. The reference in Pugachenkova & Rtveladze [1978, p. 39] is short as the work is more general. Linder [1975] gives maybe the most complete chess aspect, taking in account and the Turgunov's thoughts.

Returning to Averbach's point of view, he underlined this possible Greek influnce mainly with two points: the introduction of a war board-game and the absence of the luck [-dice] element. Myron Samsin [2002] had moved further. He examined the way of capture in the ancient board games of Greek Petteia - Polis and the Roman Ludus Latrunculorum, possibly draught-like games, with the latter considered as Polis' derivative. Taking into account some sources [that we'll see below], he set two preconditions: firstly that the way of capture in these games was the one we know for the Tafl game - a piece is removed if it's surrounded on its two opposite sides by opponent's pieces; secondly that the usual move of a piece in these games should be to move forward. With these in mind, he saw a possible evolution that led to the way of capture by a pawn in chess...

I can't be sure how true are the aforementioned thoughts, but they made me look at the Greek & Latin sources [translations are all mine, trying to make them as accurate as possible so for you to draw your own conclusions; unless it's written elseway. Complete references at the end of the post].

A. Petteia - Polis up

1. As introduction up

Petteia or pesseia [πεττεία/ πεσσεία] was a general term in ancient Greece for games, probably board ones, that were played with pieces, stones [= pessoi/ πεσσοί]. First tracked mention of pessoi as a game is made by Homer in Odyssey of the 8th c. BCE, when he describes one of the very first scenes of the epic poem taking place in the palace at Ithaca...

| οἱ μὲν ἔπειτα πεσσοῖσι προπάροιθε θυράων θυμὸν ἔτερπον ἥμενοι ἐν ῥινοῖσι βοῶν, οὓς ἔκτανον αὐτοί | Then they [=the suitors] were taking pleasure in pessoi in front of the doors, sitting on the hides of oxen that they themselves had killed. |

The reference is too plain and the kind of the piece-game of the suitors had concerned scholars since the antiquity [though some hundreds years after the poem was written]. Athenaeus of Naucratis, in his work Deipnosophistae of the early 3rd c. CE, was reproducing a lost now version that was given by an earlier Homer's commentator; Apion of Alexandria, a greco-egyptiαn grammarian born few years before the common era starts. The way it's written can let us believe that it was humorous or ironic to a degree.

| καὶ οἱ μνηστῆρες δὲ παρ᾽ αὐτῷ 'πεσσοῖσι προπάροιθε θυράων' ἐτέρποντο, οὐ παρὰ τοῦ μεγάλου Διοδώρου ἢ Θεοδώρου μαθόντες τὴν πεττείαν οὐδὲ τοῦ Μιτυληναίου Λέοντος τοῦ ἀνέκαθεν Ἀθηναίου, ὃς ἀήττητος ἦν κατὰ τὴν πεττευτικήν, ὥς φησι Φαινίας. Ἀπίων δὲ ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεὺς καὶ ἀκηκοέναι φησὶ παρὰ τοῦ Ἰθακησίου Κτήσωνος τὴν τῶν μνηστήρων πεττείαν οἵα ἦν. 'ὀκτὼ γάρ, φησί, καὶ ἑκατὸν ὄντες οἱ μνηστῆρες διετίθεσαν ψήφους ἐναντίας ἀλλήλαις, ἴσας πρὸς ἴσας τὸν ἀριθμόν ὅσοιπερ ἦσαν καὶ αὐτοί. γίνεσθαι οὖν ἑκατέρωθεν δ᾽ καὶ πεντήκοντα. τὸ δ᾽ ἀνὰ μέσον τούτων διαλιπεῖν ὀλίγον ἐν δὲ τῷ μεταιχμίῳ τούτῳ μίαν τιθέναι ψῆφον, ἣν καλεῖν μὲν αὐτοὺς Πηνελόπην, σκοπὸν δὲ ποιεῖσθαι εἲ τις βάλλοι ψήφῳ ἑτέρᾳ... | And the suitors amused themselves 'in front of the doors with pessoi', not having learnt the piece-game [petteia] from Diodorus the great or from Theodorus, neither from Leon of Mitylene, the ever since always Athenian, who was absolutely invincible at the piece-game, as Phainias says. But Apion of Alexandria says that he had heard from Cteson of Ithaca what kind of game was the piece-game of the suitors. 'The suitors, being a hundred and eight, he says, arranged their pieces opposite to one another, in equal numbers, as they themselves were. So that there were fifty[-four] on each side. And between them they left empty a small space. And in the middle they placed one piece, which they called Penelope, and they made it the goal, if one of them could strike it with his piece/stone... |

It's my feeling that the writer wanted to make the suitors look a little like fools. After all they were the bad guys of this epic.

However, the invention of the game petteia had taken a legendary form. Plato of the 5th c. BCE, gives a beautiful myth originated in Egypt, place that he probably had visited.

| ἤκουσα τοίνυν περὶ Ναύκρατιν τῆς Αἰγύπτου γενέσθαι τῶν ἐκεῖ παλαιῶν τινα θεῶν, οὗ καὶ τὸ ὄρνεον ἱερὸν ὃ δὴ καλοῦσιν Ἶβιν: αὐτῷ δὲ ὄνομα τῷ δαίμονι εἶναι Θεύθ. τοῦτον δὴ πρῶτον ἀριθμόν τε καὶ λογισμὸν εὑρεῖν καὶ γεωμετρίαν καὶ ἀστρονομίαν, ἔτι δὲ πεττείας τε καὶ κυβείας, καὶ δὴ καὶ γράμματα. βασιλέως δ᾽ αὖ τότε ὄντος Αἰγύπτου ὅλης Θαμοῦ... | So I heard that at Naucratis of Egypt, was one of the ancient gods there, whose sacred bird is called Ibis; and the name of this god is Theuth. And he invented numbers and calculation, and geometry and astronomy, also piece-games and dice-games, and especially letters. And the king of all Egypt at that time was Thamus... |

Naucratis was a Greek colony in ancient Egypt, founded in the 7th c. BCE; a place where a culture interaction occurred. However, the most important point of this passage is that Plato is using the relevant terms in plural, underlining that there were more than one kind of the piece-games. Also a contrast, or at least a distinction, between piece-games and the dice ones, is made. Similar separation is tried and by Aristoteles [Rhetoric, 1371a], where he describes as pleasant the victory in games, distinguishing them in knucklebones, balls, dice-ones and pessoi-ones; always in plural. On this distinction, Hesychius of Alexandria, trying to analyze a passage by Sophocles, was writing in his Lexicon:

| 'καὶ πεσσὰ πεντέγραμμα καὶ κύβων βολαί' Σοφοκλής Ναυπλίω Πυρκαεί, παρ' όσον πέντε γραμμαϊς έπαιζον, διαφέρει δε πετ(τ)εία κυβείας, εν ή μεν γαρ τους κύβους αναρρίπτουσίν εν δε τή πετ(τ)εία αυτό μόνον τας ψήφους μετακινούσι | 'And five-lined stones and dice throws', according to Sophocles in Nauplios Pyrkaeus [=Nauplios arsonist], as they played on five lines. And petteia [=piece/stone game] is differing from kybeia [=dice game], in which [=kybeia] they are throwing the dice. But in petteia they are moving only the pieces. |

Hesychius was writing almost 1.000 years after Plato and Sophocles, and his entry possibly is incomplete to a degree. However, it's known that he had used previous sources. The distinction he tries, isn't as accurate as it can be. We know that sometimes the terms could be mixed, as we're gonna see below. But maybe it shows that it was typical.

Footnoting: Kidd [2017b] showed with almost certainty that the word κύβος [kybos=cube, die] and its derivatives were used in antiquity not only for dice-games but in a more general way for gambling. And he actually deternimed gambling as money betting in 'any game which involves winning and losing'. The latter could actually include in kybeia-group even games that weren't played via chance. Though the wider approach of the word kybeia as gambling is totally convincing, I don't feel 100% sure that this included and games not played with some luck element [eg. in modern terms, would it be chess part of this dice-group?]. Generally important remark. But for the present approach it won't have a decisive effect. As we're looking for a total absence of the luck element in the games under question, I think that we should be more strict so to exclude it with more safety. However it made me think on the use of this term in Greek and Latin when it was related with the relevant prohibitions of the Middle Ages.

Plato placed the invention of pessoi in Egypt. However Greek tradition was different. Already since 5th c. BCE we can find texts attributing this creation to a less known hero, Palamedes...

| τίς γὰρ ἂν ἐποίησε τὸν ἀνθρώπινον βίον πόριμον ἐξ ἀπόρου καὶ κεκοσμημένον ἐξ ἀκόσμου, τάξεις τε πολεμικὰς εὑρὼν μέγιστον εἰς πλεονεκτήματα, νόμους τε γραπτοὺς φύλακας [τε] τοῦ δικαίου, γράμματά τε μνήμης ὄργανον, μέτρα τε καὶ σταθμὰ συναλλαγῶν εὐπόρους διαλλαγάς, ἀριθμόν τε χρημάτων φύλακα, πυρσούς τε κρατίστους καὶ ταχίστους ἀγγέλους, πεσσούς τε σχολῆς ἄλυπον διατριβήν; | So who made human life wealthy from poor, and ordered from disordered, finding war tactics, the biggest advantage, and written laws, guardians of justice, and letters memory's tool, and measures and weights, for rich commercial dealings, and the number, guard of money, and the torches, the best and quickest messengers, and pessoi [=game pieces], the pleasant pastime? |

It's noticeable that in some texts Palamedes invented dice along with game pieces, while in some only pessoi are mentioned. Palamedes was a hero that participated in the Trojan war; though not mentioned in the famous Homer's epics, but in other sources - versions of the Trojan war. Generally a hero with weird attributes. He was famous for his bright mind, while one of the stories goes that he tricked Odysseus, who was pretending the fool so to avoid the Trojan war, and revealed his acting. Odysseus didn't forget it and set up a trap, convincing the Achaeans that Palamedes was a traitor; and so Palamedes was condemned to death [most detailed ancient source Philostratus, Heroicus, of early 3rd c. CE, also Cypria in Proclus' Chrestomathy & Pseudo-Apollodorus' Library Epit. 3.6-3.11// for a possible transposition in Medieval literature check this previous blog].

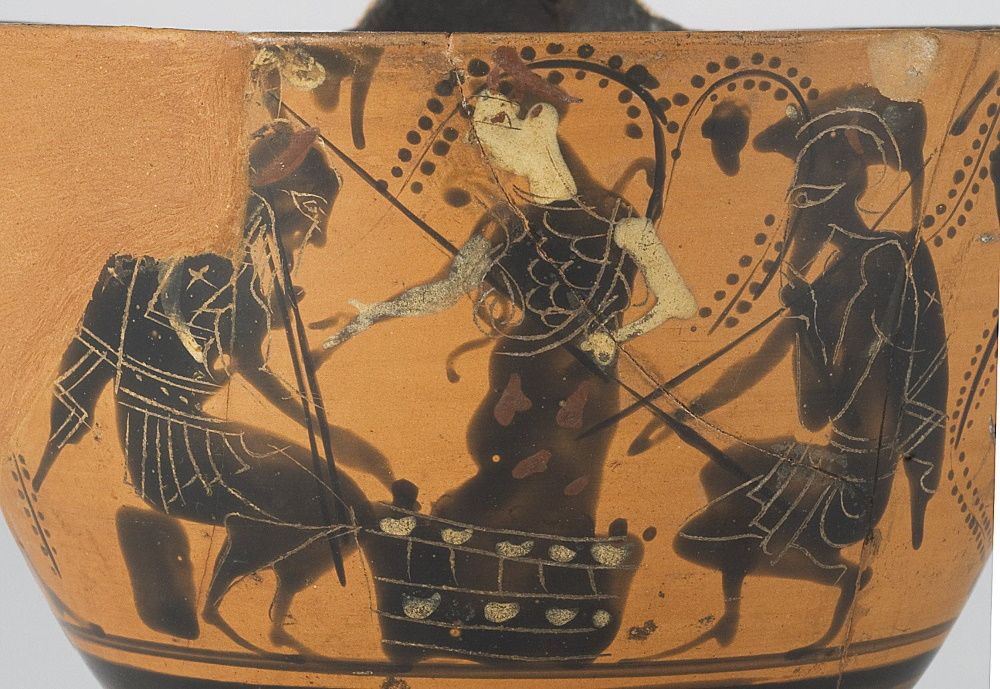

In this story Mariscal [2011] saw a possible interpretation of a scene found in ancient Greek vases since 6th c. BCE.

Over 150 vases, dated between 550-450 BCE, had been found depicting two warriors playing a board game. In some the names are written, Achilles and Ajax, two heros of the Achaeans in the Trojan War. While in fewer, numbers are written too, like the two players are announcing their dice throws. According to the story, Achilles and Ajax were Palamedes' friends and were opposed to the Achaeans' decision, refusing in the end to fight with them. So the scene may show the two of them playing instead of fighting, while the board game, sometimes possibly with dice, is a reference to Palamedes.

It's an approach that could be convincing. However, Nagy [2015] considers these vases, at least some of them, as a depiction of the theme 'Who could be the best Achaean warrior', Achilles or Ajax as the best ones; mainly based on the fact that Achilles has a stronger dice throw.

.

2. Some ancient excerpts giving general characteristics of petteia up

Some passages mainly from classical antiquity may bring some light to the kind of game that petteia could be. The problem is that are really few and can only be approached interpretatively. And we should always have in mind that there wasn't only one petteia-game.

2.1. A complicated game up

| κατεῖδον δὲ δύ᾽ Αἴαντε συνέδρω, τὸν Οἰλέως Τελαμῶνός τε γόνον, τὸν Σαλαμῖνος στέφανον· Πρωτεσίλαόν τ᾽ ἐπὶ θάκοις πεσσῶν ἡδομένους μορφαῖσι πολυπλόκοις Παλαμήδεά θ᾽, ὃν τέκε παῖς ὁ Ποσειδᾶνος... | And I saw two in council [-or just talking], one was Ajax of Oileus, the other Ajax of Telamon, the glory of Salamis· and [I saw] Protesilaus, on seats for pessoi pleased with the complicated shapes, with Palamedes, who was Poseidon's grandchild... |

This tragedy was written in 407 BCE ca. There're two points here that would need some explanation regarding translation.

Firstly the word μορφή. Originally means shape, literally as much as metaphorically. So we have a complicated shape that could please a player. Possibly the position of the pieces is meant, or a combination.

The second point is about who is playing. All agree that Protesilaus and Palamedes are in. But there're translations that involve also the two first, under the name Ajax, based on this συνέδρω, that could be translated as in council or just talking/with the company of. Hubner [2009, p. 89], suggests that was a consultation game in pairs. Something that underlines the complexity of the position. However I think that only Protesilaus and Palamedes are playing. This 'in council' refers strictly to the first two, something that isn't repeated for the second pair.

2.2. A war game up

| πολλοὺς μὲν γὰρ αὐτῶν ἐν ταῖς κατὰ μέρος χρείαις ἀποτεμνόμενος καὶ συγκλείων ὥσπερ ἀγαθὸς πεττευτὴς ἀμαχεὶ διέφθειρε | And in partial warfares, by cutting off and surrounding many of them, like a good piece-player, he [=Hamilcar] destroyed them without battle |

The text was written in the 2nd c. BCE, describing the rebellion that followed in Northern Africa, after the defeat of the Carthaginians during the 1st Punic War. More specifically around the warfares after the battle of Utica in 240 BCE; Hamilcar, who fought against the rebels, was a general of Carthage and father of Hannibal.

The comparison is clear. Petteia here is a war game of strategy. The terms 'cutting off' and 'surrounding' may deserve to be taken in account; also a piece by piece capturing could be implied, something like guerrilla warfare, though both cautiously. 'Surrounding' would fit really better in a draught-like game, rather than backgammon. The term 'without battle' may show some deepening in gameplay.

2.3. A game of leading strategy?! up

| Δαναὸς δὲ πατὴρ καὶ βούλαρχος καὶ στασίαρχος τάδε πεσσονομῶν κύδιστ᾽ ἀχέων ἐπέκρiνε φεύγειν ἀνέδην διὰ κῦμ᾽ ἅλιον, κέλσαι δ᾽ Ἄργους γαῖαν... | And father Danaos, being the advisor [=leader of a plan] and the leader of our band, arranging the pieces, decided as the best of pains to just leave through the waves of the sea, and come in the land of Argos... |

The passage is a little difficult, as Aeschylus seems toying with the words, in a play written between 490-465 BCE. While the meanings may have even some proleptic interpretation for events that would follow in the play.

Let's see the plot for a while. It's an introductory scene. Danaos, king of Libya, & his fifty daughters [Danaides], left Egypt, so to avoid a forthcoming marriage with the fifty sons of Aegyptus, Danaos' brother and king of Egypt. And asking for asylum, they arrived at Argos, where Danaos had family roots.

Our word is πεσσονομῶν [pessonomon], meaning playing with the pessoi/pieces, but with a word origin of arranging or setting [the pieces]. I think it should be approached with the other two characteristics of Danaos, βούλαρχος and στασίαρχος [voularchos, stasiarchos]. The first is translated as advisor or leader of a plan, but it's also a word used for the president of a local senate in few cases. The second is translated as leader of a band, possibly with a meaning of revolted/outlaw. I believe that the basic element we should see is the 2nd component of both of these characteristics; meaning that Danaos is -αρχος [-archos] of something, that stands for leading power. A leader arranges the pieces. Almost a clear reference of petteia as a strategy game.

Footnoting: Bakewell [2008] commenting on this passage, adopted inter alia some political approach used by Kurke [1999a, 1999b]. Kurke tried an interesting explanation of the games of petteia with political terms. But connecting a certain type of petteia game, with a specific ideology, within a dualistic pair democracy-oligarchy [1999a, p. 265]; approach that isn't repeated with the same terms in the 1999b paper. However, such a strict connection, between a specific kind of game with a particular political system, may raise some questionning.

2.4. A king's game, as the science of ruling up

| -ἐξ ἀνάγκης δὴ νῦν τοῦτο οὕτω σκεπτέον, ἐν τίνι ποτὲ τούτων ἐπιστήμη συμβαίνει γίγνεσθαι περὶ ἀνθρώπων ἀρχῆς, σχεδὸν τῆς χαλεπωτάτης καὶ μεγίστης κτήσασθαι. δεῖ γὰρ ἰδεῖν αὐτήν, ἵνα θεασώμεθα τίνας ἀφαιρετέον ἀπὸ τοῦ φρονίμου βασιλέως, οἳ προσποιοῦνται μὲν εἶναι πολιτικοὶ καὶ πείθουσι πολλούς, εἰσὶ δὲ οὐδαμῶς. -δεῖ γὰρ δὴ ποιεῖν τοῦτο, ὡς ὁ λόγος ἡμῖν προείρηκεν. -μῶν οὖν δοκεῖ πλῆθός γε ἐν πόλει ταύτην τὴν ἐπιστήμην δυνατὸν εἶναι κτήσασθαι; -καὶ πῶς; -ἀλλ᾽ ἆρα ἐν χιλιάνδρῳ πόλει δυνατὸν ἑκατόν τινας ἢ καὶ πεντήκοντα αὐτὴν ἱκανῶς κτήσασθαι; -ῥᾴστη μεντἂν οὕτω γ᾽ εἴη πασῶν τῶν τεχνῶν: ἴσμεν γὰρ ὅτι χιλίων ἀνδρῶν ἄκροι πεττευταὶ τοσοῦτοι πρὸς τοὺς ἐν τοῖς ἄλλοις Ἕλλησιν οὐκ ἂν γένοιντό ποτε, μή τι δὴ βασιλῆς γε. |

- Necessarily, then, this we should now think, in which, if any, of these sciences occurs the one of ruling men, almost the hardest and greatest to acquire. As we must discover it, so that to see whom of the men we should remove from the wise king, who pretend to be statesmen and convince many that they are, but aren't at all. - We should do this, as it was implied [=said] in our conversation. - Would it seem possible the crowd in a city-state to acquire this science? - How? - Would it, perhaps, be possible in a city of one thousand men, a hundred, or even fifty, to acquire it sufficiently? - This way it would be the easiest of all the arts· as we know that, among other Greeks, would never occur so many excellent pessoi-players in one thousand men, let alone kings. |

A clear passage. Good pessoi-players are rare and like rulers, or at least like ones who know how to rule. This could also be a loose allusion of the game πόλις [polis], a type of petteia games; and this as the game of petteia is mentioned along with or around the word. Suffice it to say now that the word, πόλις, originally meaning city but also state, has been tracked in some excerpts where meanings around it are analyzed and presented with examples or expressions containing some game of petteia [of which some cases we'll see under A.5.2].

2.5. No legal moves or zugzwang - as a strategy?! up

| ...καὶ ὥσπερ ὑπὸ τῶν πεττεύειν δεινῶν οἱ μὴ τελευτῶντες ἀποκλείονται καὶ οὐκ ἔχουσιν ὅτι φέρωσιν, οὕτω καὶ σφεῖς τελευτῶντες ἀποκλείεσθαι καὶ οὐκ ἔχειν ὅτι λέγωσιν ὑπὸ πεττείας αὖ ταύτης τινὸς ἑτέρας, οὐκ ἐν ψήφοις ἀλλ᾽ ἐν λόγοις. | ... and just like the unskilled [players] in the end [=finishing], are shut out [=blocked, trapped] by the experts in pessoi and don't have what to play [=lead/ direct], in the same way and those [previously mentioned], in the end [=finishing], are blocked and don't have what to say by this other game of petteia, not with counters but with words. |

A really interesting passage that probably shows some specific strategy in some game with pessoi, but has some difficulties with its translation.

Here Plato likens some game of petteia to a dialectic process, where a step by step questioning and answering could mislead to a wrong result, seemingly agreeing with one's primal correct thesis. And the debator can't continue his arguments, like in a petteia game there could be a situation where a player has nothing to move, to play. The verb that is used is ἀποκλείονται, literally meaning being prevented to move, being shut out or shut up, so blocked, trapped, imprisoned. This has been translated by some writers as cornered, resembling to a draught-like or even a chess-like situation and underlining a possible connection. However, this can't be accurate. Being blocked, either as in a no legal move situation or as in zugzwang, can be seen in the backgammon game, as well as in draughts or chess. But in any case shows some deepening in the gameplay strategy.

However, possibly no luck element is implied here. This as the blocked position has occurred primarily after the losing player's moves, who is misled; if there're dice in, there could be not a save by them.

It's difficult to see whether this blocking signifies the end of the game, something like stalemate. The participle τελευτῶντες [=finishing] strictly has as subject the weak players or/and talkers, so here most probably they are finishing their set of moves - combinations, not the game. On this maybe light could bring the following passage, attributed with doubt to Plato again, but which is considered spurious [for a philological comparison of these two texts, check Donato [2016]].

| Ἴσως γάρ, ἦν δ᾿ ἐγώ, σὺ οἴει, ὦ Ἐρυξία, τουτουσὶ μὲν τοὺς λόγους, οὓς νυνὶ διαλεγόμεθα, εἶναι παιδιάν, ἐπεὶ οὐκ ἀληθῶς γε οὕτως ἔχειν, ἀλλ᾿ ὥσπερ ἐν τῇ πεττείᾳ εἶναι πεττούς, οὓς εἴ τις φέροιτο, δύναιτ᾿ ἂν τοὺς ἀντιπαίζοντας ποιεῖν ἡττᾶσθαι οὕτως ὥστε μὴ ἔχειν ὅτι πρὸς ταῦτα ἀντιφέρωσιν. | Perhaps, I said, you think, Eryxias, that these words, which we are now saying to each other, are [just] a game, as [you think] they aren't true, but just like in petteia [you think that] they are pessoi, that, if one moves them, he could make his opponents weaker, so that they don't have what to counterplay. |

Here pessoi are compared again with words, but the meaning is obviously more negative. The writer seems believing that there's some truth beyond arguments in words, while on the contrary in the game of petteia the truth is just on the board. The passage signifies that the situation where there's no counterplay, is just an inferior position. Not a defeat exactly. The word that is used is ἡττᾶσθαι, originally meaning being defeated but also being weaker, inferior, dominated, overcome. If we choose to translate as defeat, then the meaning becomes irrational due to the structure of the sentence. Cause the inability of counterplay is set as a conclusion of this ἡττᾶσθαι [=being defeated or weaker]; and losing just ends the game. The translation of being weaker feels really better.

2.6. A clever game up

| ὄντων δὲ τῶν Ἀχαιῶν ἐν Αὐλίδι πεττοὺς εὗρεν οὐ ῥᾴθυμον παιδιάν, ἀλλ᾽ ἀγχίνουν τε καὶ ἔσω σπουδῆς. | And while the Achaeans were in Aulis, he [Palamedes] invented pessoi, which is not a frivolous [= easy] pastime, but a shrewd and of inside zeal [= pains, trouble, effort]. |

A later text of the early 3rd c. CE, and without the need of any further explanation

2.7. Compared with geometry and calculation up

| ἕτεραι δέ γέ εἰσι τῶν τεχνῶν αἳ διὰ λόγου πᾶν περαίνουσι, καὶ ἔργου ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν ἢ οὐδενὸς προσδέονται ἢ βραχέος πάνυ, οἷον ἡ ἀριθμητικὴ καὶ λογιστικὴ καὶ γεωμετρικὴ καὶ πεττευτική γε καὶ ἄλλαι πολλαὶ τέχναι, ὧν ἔνιαι σχεδόν τι ἴσους τοὺς λόγους ἔχουσι ταῖς πράξεσιν, αἱ δὲ πολλαὶ πλείους, καὶ τὸ παράπαν πᾶσα ἡ πρᾶξις καὶ τὸ κῦρος αὐταῖς διὰ λόγων ἐστίν. | But there're and others of the arts, that accomplish their whole purpose though reasoning [= logic, reckoning, speech, word], and - as it's said briefly - they aren't attached to any action or very little· such as [the arts of] arithmetic and calculation and geometry and pessoi and many other arts, of which some have equal the reasonings to the actions, but the most of them [have the reasonings] more, and absolutely every action and their value [= power, validity] exists trough reasonings. |

Here the game of pessoi is in the same group of arts like arithmetic, calculation and geometry. I don't feel 100% sure if this connection signifies a deep thinking/calculation or just a calculation of the dice throws. At first it could be both. However, a calculation of dice throws compared with geometry seems really really inferior.

A translation problem here could be the word λόγος [logos]. It originally means speech, word, and this way we will find most of the passage's translations. However it also means reasoning, logic, reckoning. The problem is that the main object of this Plato's dialogue is the rhetoric art, so speech/word should be a first choice. But this λόγος [or even in plural] is characteristic of arithmetic and geometry, too. So if we would choose to translate as word, the thinking process [through words] should be meant firstly or at least implied. I believe that here Plato is toying with the word to a degree, actually letting both meanings to be understood.

Footnoting: The comparison between the petteia game and geometry reminds the relevant entry of 'petteia' in the Lexicon of Platonic words, possibly edited by some Timaeus the Sophist of the first centuries CE. There it was written that geometry was another way to call petteia in Platonic dialogues. However generally the origins of this work as a whole, as well as of each entry seperately, is under question.

2.8. First impression up

Having in mind that there were probably more than one games in the group of petteia, here we have: a war-game, a complicated game, a strategic one, one resembling to the art of ruling, one for smart guys, and an other compared with geometry. Well I feel almost sure that at least one of them would be played without dice. Besides the fact that nowhere here dice are implied, especially the art of ruling should exclude a chance element. Also Polybius' description of petteia as a war game [text 07] is rather incompatible with chance.

However, even if the above descriptions could convince us around a non-chance element [something that will be confirmed and below, under A.5.c], we can't be 100% sure that they are referring to the firt appearance of non-dice games; they possibly could just be the first textual allusions. In my mind there was the case of the game under the tile Nine men's morris, that mainly was played without dice. Around it they have been given some possible really ancient first dates, since 2nd millenium BCE. But they have been questioned convincingly, placing the first findings in Roman sites of the 1st c. BCE [Berger [2004], p. 15, also discussion in Kevin & Brent Moberly in Classen [2019], p. 711ff].

In any case, maybe the possible indisputable step in game evolution that was made here with petteia, was a non-dice game played on an open board; something that would let human imagination free.

.

3. Julius Pollux: the earliest surviving games' description of the 2nd c. CE up

Onomasticon, an important work, was originally written before the end of 2nd c. CE by Julius Pollux, a Greek scholar and rhetorician from Naucratis of Ancient Egypt. According to Philostratus, writing almost a century after in his Lives of Sophists [Βίοι Σοφιστών], Pollux was nominated as a professor in the Academy of Athens by Roman emperor Commodus; however Philostratus is questioning to a degree Pollux's education, without being exactly positive or negative.

Unfortunately Pollux's work seems to be a compendium of his original one, written or compiled towards the end of 9th c. CE, by Arethas, Archbishop of Caesarea, but also a book collector and scholar-theologian of the Greek Orthodox Church, who saved many works from classical antiquity [inter alia check this online Review by Philip Rance, also Erich Bethe's introduction - in Latin - in Pollucis Onomasticon, vol. 1, 1900].

|

τὰ μὲν οὖν ἐργαλεῖα τὰ κυβευτικὰ ἐν τοῖς περὶ τεχνῶν, ̓ἔστι προειρημένα, τὸ δὲ πεττεύειν καὶ ἡ πεττεία, καὶ τὸ πεσσονομεῖν καὶ ὁ πεττευτής, καὶ ταῦτα μὲν ἐπ' ἐκείνοις προείρηται· ἐπεὶ δὲ ψῆφοι μέν εἰσιν οἱ πεττοί, πέντε δ' ἑκάτερος τῶν παιζόντων εἶχεν ἐπὶ πέντε γραμμῶν, εἰκότως εἴρηται Σοφοκλεῖ 'καὶ πεσσὰ πεντέγραμμα καὶ κύβων βολαί'. τῶν δὲ πέντε τῶν ἑκατέρωθεν γραμμῶν μέση τις ἦν ἱερὰ καλουμένη γραμμή· καὶ ὁ τὸν ἐκεῖθεν κινῶν πεττὸν παροιμίαν 'κίνει τὸν ἀφ' ἱερᾶς'. ἡ δὲ διὰ πολλῶν ψήφων παιδιὰ πλινθίον ἐστί, χώρας ἐν γραμμαῖς ἔχον διακειμένας· καὶ τὸ μὲν πλινθίον καλεῖται πόλις, τῶν δὲ ψήφων ἑκάστη κύων· διῃρημένων δὲ εἰς δύο τῶν ψήφων κατὰ τὰς χρόας, ἡ τέχνη τῆς παιδιᾶς ἐστὶ περιλήψει δύο ψήφων ὁμοχρόων τὴν ἑτερόχρων ἀνελεῖν· ὅθεν καὶ Κρατίνῳ πέπαικται 'Πανδιονίδα πόλεως βασιλέως τῆς ἐριβώλακος, οἶσθ' ἣν λέγομεν, καὶ κύνα καὶ πόλιν, ἣν παίζουσιν'. ἐγγὺς δέ ἐστι ταύτῃ τῇ παιδιᾷ καὶ ὁ διὰγραμμισμὸς καὶ τὸ διαγραμμίζειν, ἥντινα παιδιὰν καὶ γραμμὰς ὠνόμαζον. |

And the dice tools are already described in [the chapter] on the arts, and petteuein [=playing with pieces] and petteia [=piece-game] and pessonomein [=arranging pieces] and petteutis [=piece player] and these around them have been already told; and as pessoi are pieces, and each of the two players had five on five lines, properly is said by Sophocles: 'and pessa pentegramma [=five-lined stones] and dice throws'. and of the five lines on each side, there's one line in the middle called sacred· and the one who moves the stone from there according to the proverb: 'moves the from the sacred line [stone]'. And the game with many pieces is a plinthion [=board], that has fields [=lands, spaces, squares] lying in between lines· and the board is called polis [=city], and each of the pieces kyon [=dog]· and as the pieces are divided in two according to the color, the art [=way of playing] of the game is in summary that two pieces of the same color eliminate [=destroy, kill] the one of different color· from where and by Cratinus was played [=told in a play]: 'Son of Pandion King of the fertile city, you know the one that we mean, and the dog and the city, that they play'. And close to this game is diagrammismos [=action/product of dividing with lines] and diagrammizein [=dividing with lines], game that is called also lines. |

So here we have three games played with pessoi:

- One that we'll call Five Lines [= Pente Grammai] for ease [under A.4.]. I won't deepen too much in it. It's presented mostly for completeness and comparisons.

- One propably called Polis [under A.5.], that is my main target.

- And one similar to the latter, that is called Diagrammismos [also under A.5. in some points for comparison with polis].

.

4. Five Lines - Pente Grammai up

Pollux, in 2nd c. CE, seems to be the first mentioning this early reference of the game, pessa pentegramma [=five-lined stones], but, according to what he was writing, found in a Sophocles' tragedy of the 5th c. BCE. Hesychius, almost 400 years after Pollux, is making the same reference [in text 04], but he's giving the name of the tragedy too, Nauplios Pyrkaeus. It has been traced that Hesychius was sometimes copying entries of previous lexicographic works, but here the new element of the name of the tragedy can signify either that both, Pollux and Hesychius, were consulting a third independent previous source, or that Hesychius had in hand a possible more complete Pollux's work. In any case the addition of the name of the Sophocles' play gives a validity to the source.

Pollux, in an other entry of his work [VII 206], is classifying the game among the ones that were played with dice, though in a descriptive way, using actually only the phrase 'the sacred line'. But a phrase that could refer only to this game in his work. A case where petteia [piece-games] and kybeia [dice-games] are crossed.

The dice element can be confirmed by archaelogical finds, too. Schädler has given some really interesting items in his of 2009 paper. One of them is the following [fig.07], discovered in a tomb in Anagyros, Attiki, Greece. It's a gaming table with five parallel lines on it and four mourning women on each edge, dated in 7th c. BCE, and accompanied by a die. We know from a mourning poem attributed to Pindar [of 5th c. BCE] that there should be a belief around dead, who were amused in playing with pessoi in the afterlife.

Pollux seems also to be the fist in literature matching the aforementioned Sophocles' proverb of 'five lines' with the probably ancient proverb of 'moving the from the sacred line stone' [=the middle line]. Phrases that were repeated and analyzed by Eustathius, Archbishop of Thessalonica, in his comments on Homer's Odyssey, too. Specifically he was writing:

| ὁ δὲ τὰ περὶ Ἑλληνικῆς παιδιᾶς γράψας... τοὺς δὲ πεσσοὺς λέγει, ψήφους εἶναι πέντε. αἷς ἐπὶ πέντε γραμμῶν ἔπαιζον ἑκατέρωθεν, ἵνα ἕκαστος τῶν πεττευόντων ἔχῃ τὰς καθ᾽ ἑαυτόν. Σοφοκλῆς. καὶ πεσσὰ πεντάγραμμα καὶ κύβων βολαί. παρετείνετο δέ φησι δι᾽ αὐτῶν, καὶ μέση γραμμή. ἣν ἱερὰν ὠνόμαζον ὡς ἀνωτέρω δηλοῦται, ἐπεὶ ὁ νικώμενος, ἐπ᾽ ἐσχάτην αὐτὴν ἵεται. ὃθεν καὶ παροιμία, κινεῖν τὸν ἀφ᾽ ἱερᾶς, λίθον δηλαδὴ, ἐπὶ τῶν ἀπεγνωσμένων καὶ ἐσχάτης βοηθείας δεομένων. Σώφρων. κινήσω δ᾽ ἤδη καὶ τὸν ἀφ᾽ ἱερᾶς. Ἀλκαῖος δέ φησιν ἐκ πλήρους, νῦν δ᾽ οὗτος ἐπικρέκ[τ]ει κινήσας τὸν πείρας πυκινὸν λίθον. τοιοῦτον δὲ καὶ παρὰ Θεοκρίτῳ τὸ, τὸν ἀπὸ γραμμᾶς κινήσω λίθον. Διοδώρου δέ φησι τοῦ Μεγαρικοῦ ἐνάγοντος τὸν τοιοῦτον λίθον εἰς ὁμοιότητα τῆς τῶν ἄστρων χορείας, Κλέαρχος τοῖς πέντε φησί πλάνησιν ἀναλογεῖν. | The one who wrote on the Greek game... says that pessoi are five pieces. which were played on five lines on each side, so each of the players has his own [lines, most probably]. Sophocles. and five lined stones and dice throws. and it's lying among them, he says, a middle line. which they called sacred as it's mentioned above, as the loser moves it at last. from where and the proverb, 'moving the from the sacred', that is stone, for the desperated and the ones asking for the last chance help. Sophron. I'll move now the from the sacred. And Alcaeus says it fully, 'now he prevails, moving the from sacred compact [<-possible translation] stone'. and the same by Theocritus the [proverb], 'I'll move the from the lines stone'. And he says that, though Diodorus of Megara was likening this kind of stone to the orbit [=literally 'dance'] of the stars, Clearchus says that [the five pieces] correspond to the five planets. |

Firstly it should be underlined that Eustathius lived in the 12th c. CE. But his mentioned prime source is 'the one who wrote On the Greek game'. A lost now work whose author has been identified as Roman Suetonius of 1st c. CE [check eg. Wardle [1993]]. For me it's not clear enough if the proverbs that followed, are taken all from Suetonius' work or Eustathius was using other even earlier sources. This repeated 'says' has not always a clear subject. However the mainstream approach is that were all given by Suetonius [check eg. Kidd [2017a], where generally an approach on the references for this game, though I have doubts on one by Aristotle, that will be mentioned below].

Just a short list of the by Eustathius mentioned here names: Sophocles, tragedian of 5th c. BCE, Sophron of Syracuse, writer of dialogues with comic elements and mimes, of 5th c. BCE, Alcaeus of Mytilene, lyric poet of the 7th c. BCE, Theocritus, Sicilian poet of the 3rd c. BCE, Diodorus Cronus of the Megarian philosophy school of 4th-3rd c. BCE, Clearchus of Soli - Cyprus, philosopher of the 4th–3rd c. BCE.

To these it should surely be added one line by Plato.

| ἡ δὴ τὸ μετὰ τοῦτο φορά, καθάπερ πεττῶν ἀφ᾽ ἱεροῦ, τῆς τῶν νόμων κατασκευῆς, ἀήθης οὖσα, τάχ᾽ ἂν θαυμάσαι τὸν ἀκούοντα τὸ πρῶτον ποιήσειεν. | The next move on the law construction, being unusual just like of pessoi of the sacred, might cause surpise to the one who would hear it for first time. |

Not sure if it was unusual to move from the sacred line [=rare], or the move was unusual [=different]. Kidd's in parallel analysis of the aforementioned Alcaeus' passage shows that moving a stone from the sacred line may have special attributes, that could change the game's outcome.

In any case, with these and more in mind and though Murray's approach was different [1952, p. 28], the game seems to be in general a backgammon-like one, played with dice, on a board of five lines [or more of odd number], with pieces moving on them possibly on the same direction-orbit [like planets], and with a possible ultimate goal this sacred line in the middle [mainly, Schädler [2009] & Kidd [2017a]].

.

5. Polis up

Repeating Pollux so to start:

And the game with many pieces is a plinthion [=board], that has fields [=lands, spaces, squares] lying in between lines· and the board is called polis [=city], and each of the pieces kyon [=dog]· and as the pieces are divided in two according to the color, the art [=way of playing] of the game is in summary that two pieces of the same color eliminate [=destroy, kill] the one of different color· from where and by Cratinus was played [=told in a play]:

'Son of Pandion King of the fertile city, you know the one that we mean, and the dog and the city, that they play'.

So let's see the given characteristics one by one:

a. The game is played with many pieces. This 'many' comes after a description of another game that was played with five stones. So probably Polis was played with more than five pieces on each side. The piece is called κύων [kyon = dog].

Diagrammismos was probably played with even more pieces. Pollux doesn't mention it, but Hesychius in the 6th c. CE describes it as played with '60 pieces, white and black, drawn [dragged] into fields'.

b. We have a game played on a board called πόλις [polis, city], probably with squares, as 'fields lying between lines'. The square element is underlined also by the chosen word πλινθίον [plinthion], a word derived from πλίνθος that literally means brick, signifying either a board-frame with little bricks or a bigger squared board [or both]. To have a clue, it's also a word [plinthion] that has been used to signify a squared-rectangular formation of soldiers in battle.

The fact that there were these kind of gaming-boards in ancient Greece can be seen in all four of the following photos [fig. 09, 10, 11, 12]. The following fig. 09 specifically is an artifact found in the archealogical area of Pella, Greece, now exposed in the local museum. Ignatiadou describes it as 'a turquoise faience plaque with a plain grid of 11x11 squares, from Pella; it is exhibited with twelve glass counters that may or may not belong together' [in Ignatiadou [2019], pp. 145 & 152, where also a list of items and a photo of another smaller marble board, p. 146, of 3rd-2nd c. BCE, in Arch. Mus. of Abdera].

Unfortunately she doesn't give a picture of this board. The following is a compilation of two shots found in web, and picked according to the description. Without finding an official presentation I couldn't either identify in a certain way the exact dating of it. Ignatiadou sets it with a question mark in the Hellenistic period, that is mainly during the 4th-2nd centuries BCE.

The item of fig. 10 & 11 is clear. A gaming scene made of terracotta. Two playing on a checker board with pieces and without the presence of dice, while a third is watching. It was dug out in the area of Athens in the 19th c, now in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Unfortunately not in the permanent exhibition. Archaeological websites are dating it in the 1st c. CE.

c. Dice. Pollux doesn't mention the use of dice or knucklebones for the game Polis. In a previous entry of his Onomasticon [VII 206], is listing games played with the help of dice. There as we've seen Pente Grammai are given. Also Diagrammismos, the game that was close to Polis. However Polis not. [There's also an allusion of Diagrammismos as a dice-game, in a fragment by Philemon, a comedian playwright of 4th c. BCE, mentioned by Eustathius in Iliad's comments, rh.Z'/v.169].

Kidd [2017b] indicated convincingly and specifically with examples, that this Pollux's list of dice-games in the VII 206 entry, doesn't include strictly dice-games only, but generally gambling-ones. However he suggests further that by the term gambling [=kybeia] Pollux was meaning mostly the money-betting feature. This could let us have the impression that games played without the help of chance could be part of gambling, if they were played for money. And this would be really useful for our current approach, so to show that Polis and other games weren't played via chance, even if kyboi [=dice] are mentioned. However I think that is better to remain more strict on this very latter approach, so to seem more convincing. The fact that Polis-game isn't included in the Pollux's dice-list should be sufficient for now.

Further, in the current entry of IX 99, the knucklebones' description is following, and Polis isn't mentioned or implied at all, again; underlining the total absence of the luck-element for this particular game according to Pollux. Eustathius of the 12th c. CE, gives a different version involving knucklebones, that will be discussed below [under A.5.1].

d. The way of capture seems to be similar with the Roman Ludus Latrunculorum and Northern Tafl. Two pieces can eliminate one of the opponent's. Though it isn't mentioned exactly if these two attacking pieces should be on the opposite sides of the target-piece. Hubner [2009, p. 88] suggests that this was a Pollux's loan from descriptions of the Roman game in Ovid, and not the game's original method of play. We will be back on this [under A.5.2.3 & A.5.3].

e. There's a clear reference of a comical play written by Cratinus of the 5th c. BCE, where the game polis is mentioned, something that justifies at least the existence of the game since then. Cratinus' passage seems to be given and in earlier writings. Zenobius of the 2nd c. CE but surely earlier than Pollux, wrote a compedium of proverbs that were given by Didymus Chalcenterus of Alexandria, 1st c. BCE, and by Lucillus of Tarrha [Crete], 1st c. CE.

| Πόλεις παίζειν: μέμνηται ταύτης Κρατῖνος ἐν Δραπέτισιν· ἡ δὲ πόλις εἶδός ἐστι παιδιᾶς πεττευτικῆς. Καὶ δοκεῖ μετενηνέχθαι ἀπὸ τῶν ταῖς ψήφοις παιζόντων, ταῖς λεγομέναις νῦν χώραις, τότε δὲ πόλεσιν. | Playing cities [poleis]: Cratinus remembers it in Drapetisin [=Run-away women]; and the city is a kind of piece-game. And it seems that was transferred [the name] from the players of the pieces, that are called now fields, then [were called] cities. |

The proverb seems to be given in a different way. In singular by Pollux, in plural by Zenobius. And Pollux names the board as polis [=city], while Zenobius the pieces as poleis [=cities]. Pollux's proverb is bigger. Maybe it was just a repetition in the same play. However, it underlines that they didn't copy each other, but there should be at least one other third earlier source. Zenobius mentions also the name of the theatrical play, fact that adds more validity. It's also important that dice, or generally the luck-element, isn't mentioned or implied at all, again. Generally the passage gives the impression of an old game that had survived; as the change of the piece-names indicates.

Footnoting: One interesting thing is that the expression in Pollux goes 'and the dog and the city, that they play' [see above, text 14]. The relative clause that starts with 'that' in the ancient text refers only to 'city', as the relative pronoun [introducing the relative clause] 'ἣν' is of feminine gender like πόλις [city], while κύων [dog] is masculine. Something that may cause questioning if these are two different games; the whole phrase would probably need a neutral gender. If I would read it in an historical text I would feel more sure for this approach, however, as it's written in a comical play, maybe it's just given for a comic emphasis. The word 'dog' [=κύνα] is probably referring to a game-piece. The knucklebone throw [check below under A.5.1] bearing the same name seems less possible, as here it's in singular.

5.1. The problematic Eustathius' comments on the game Polis up

Eustathius, a Byzantine Greek scholar and Archbishop of Thessalonica, gave some confusing information. Possibly the fact that he was writing in the 12th c. CE, hundreds of years after, had played its part. Commenting on the Homer's lines on pessoi [text 01], wrote on Polis:

| ὁ τὰ περὶ τῆς καθ' Ἕλληνας παιδιᾶς γράψας... περὶ δὲ τοῦ εἰρημένου κυνὸς, κἀκεῖνο λέγει αὐτὸς γραφὲν καὶ ἀλλαχοῦ, ὅτι εἶδός τι κυβεὶας, καὶ πόλις· ἐν ᾗ ψήφων πολλῶν ἐν διαγεγραμμέναις τισὶ χώραις κειμένων, ἐγίνετο ἀνταναίρεσις· καὶ ἐκαλοῦντο αἱ μὲν γραμμικαὶ χῶραι, πόλεις ἀστειότερον· αἱ δὲ ἀντεπιβουλεύουσαι ἀλλήλαις ψῆφοι, κύνες διἀ τὸ δῆθεν ἀναιδές. Ὅτι δὲ καὶ τις βόλος ἀστραγαλιστικὸς, κύων ἐκαλεῖτο, προδεδήλωται. | The one who wrote on the pastime [=game] of Greeks... and around the aforementioned dog, he says and that [<-pronoun], which is written and elsewhere, that [<-conjunction, that-clause] it's a kind of dice-game, and a city; in which, as many pieces lying on some divided with lines fields, occurs [ant-]elimination. and the drawn by lines fields are called poleis [=cities], for [seeming] more funny. and the pieces that are planning against one another, [are called] kynes [=dogs], for [seeming] supposedly rude. And that some knucklebone throw is called dog, has already been said. |

These information of Eustathius on the game Polis seem coming again from Suetonius of the 1st c. CE. The passage comes right after an entry on knucklebones, where a throw, the '1', is also called dog [=kyon, κύων]. Compared to the Pollux's text, Eustathius gives the reason of the names. But also gives/repeats the term ἀνταναίρεσις [antanairesis], as the main action of the game. ἀνταναίρεσις, a rare term, is a compound word, 2nd element is ἀναίρεσις, same word-root found and in Pollux, translated as killing, eliminating, destroying. 1st element is the preposition ἀντ(ὶ), with prime meanings 'against' or 'instead'. However Liddell & Scott lexicon gives the whole word ἀνταναίρεσις as meaning here 'alternate removal'. The term removal is ok. But I believe that anti [=ἀντ(ὶ)] here could retain its prime translation as 'instead'. Meaning removal instead of a move, more literal, or, more allegorically, removal taking the piece's place.

The big problem with this entry is that Eustathius seems classifying the game Polis among the dice-games, or the knuckldbone ones; coming somehow in opposition with the earlier Pollux's and Zenobius' writings [texts 14 & 17]. The Kidd's approach [2017b], that κυβεὶα could stand for all the gambling-game group, doesn't seem possible to be applied here. Before this entry, precedes a comparison-similarity between knucklebones and dice [='ὁμοίως κύβῳ'] based on the fact that knucklebone is like a four-sided die. Thus the term [=κυβεὶα, dice-games] seems to have a more literal meaning here, rather than a wider approach. However syntax and grammar of this Eustathius' entry combined with possible meanings could be a real problem, too, but better to put this aside, as analysis would make things just more complicated.

Footnoting: Suffice to say here that the term πόλις [polis] seems at first to be component of the first sentence where the dice are mentioned [fact on which the confusion is based], but kinda separated and at the end of the sentence, maybe a little as a foreign part. It seems better belonging semantically to the following sentence where the term is explained. This assumption is strongly underlined by the punctuation found in the manuscripts. In P1 of the 12th-13th c. CE [BNF Grec ms 2702, f. 9r] the word is separated with a comma from the first senctence and with a mid-point from the following sentence [as in the text 18 that I give above]; but in P2, a later manuscript of the 16th c. CE [BNF Grec ms 2703, f. 18v], which is considered partially copy of the previous, the term πόλις [polis] is separated with a mid-point from the previous sentence and with not any sign from the following, signifying that it belongs only to the explanatory 2nd sentence; like a correction [?]. However P1 is considered an autograph by Eustathius, though not for official showing, but rather personal. So can't be sure of anything, just for the fact that the interpreter or transcriptor of this passage seems facing the same difficulties since 16th c. CE. And it has been also noted that P1 had passed through other hands that added mainly marginal comments; a mid-point wouldn't be such a notable addition, while these specific words in the early ms seem a little damaged, like more ink had poured. Further, another manuscript of the 14th-15th c., L: [Laurenz. MS Plut. 59.06, f. 16r], has a similar with P2 'corrected' punctuation; the term polis is seperated with a comma from the previous sentence and not at all with the next one. This L manuscript is a copy of another autograph M: [Marc. Gr. Z. 460 (=330)] of 12th c., of which unfortunately I couldn't track an online copy. So my search ends here. According to these, the early transcriptors saw in Eustathius' personal notes that the term polis should belong to the next sentence [for general approach of these manuscripts, Makrinos [2005 & 2007] & Cullhed [2012 & 2016]].

A possible answer to this classification is that Eustathius was writing only 'around the aforementioned dog'. Statement repeated and after the description of the game Polis. So Schädler [2002] considers this passage just part of a context. The assumption, that in text 18 there's just a logical connotation, could be signified, too, by the statements that the knucklebone throw '1' is called dog, and so the game pieces in Polis; but the latter not cause of a possible connection with the knucklebones. It's just so to seem supposedly rude, brash.

Schädler, in his of 2012 paper, also suggests that 'Eusthathius was confused by the double meaning of dog as a counter in polis and as a throw in dice games', taking in account and an other Eustathius' passage [text 20]. With this approach may come along, the naming of the knucklebones' throws by Greeks and Romans.

| me quoque per talos Venerem quaerente secundos semper damnosi subsiluere canes | And as I was looking for Venus through my second knucklebones, the injurious dogs have always come out |

At least at three instances in Latin literature, one can read about these 'damnosi canes' [=injurious dogs]. Specifically once in Sextus Propertius and twice in Ovid, all of the 1st c. BCE [Propertius, Elegiae 4, VIII, v. 46 - Ovid, Ars Amatoria, II, v. 206 - Ovid, Tristia, v. 474]. Something that may show a possibility of mistransliteration or just a confusion, either by Eustathius or even in a source he used; just a possibility with doubts of course. However it's underlined by the fact that 'dogs' seems to be the only common name as a knucklebone throw, both in Greeks and Romans; the rest seem altered [eg. Venus was the best Roman throw, while Euripides probably the best Greek one].

But Eustathius is writing again on the game Polis in his comments. This time directly in connection with knucklebones.

| ... δηλοῖ δὲ ὁ ῥηθεὶς κύων βόλος ἁνταναίρεσίν τινα ψήφου· ἐν χώραις γάρ τισι διαγεγραμμέναις πεττευτικῶς, πολλῶν κειμένων ψήφων, ἅς ἐχρῆν ἀνταναιρεῖν, αἱ μὲν χῶραι πόλεις ἐλέγοντο νόμῳ κυβευτικῷ, κύνες δὲ αἱ ἀλλήλαις ἀντεπιβουλεύουσαι ψῆφοι. | ... and the said throw dog signifies the [ant-]elimination of some piece, and while many pieces lying in some fields drawn by lines in the petteia way, which [pieces] one should [ant-]eliminate, the fields are called cities according to the dice rule, and the pieces that are planning against one another [are called] dogs. |

Comparing the two texts [18 & 20], they're like been written by the same person but at different periods of his life. Opposed information, or at least altered, are given. Sounds also weird the saying that the game was played on a board for a petteia-game, while the fields were called cities [=Poleis] according to the dice rule; a mixing between piece-game and dice-game rules is premised. But the biggest contradiction is that, in text 18, the fields are called cities so to seem more funny, while in text 20, are named this way just according to the aforementioned dice-rule. Is it implied here that were called and played elseway according to some other rule, like a petteia piece-rule? It seems like Eustathius is just using two different sources.

Footnoting: In accordance with this, Eustathius gives Suetonius as his source for the first text [18], while none for the second [20]. One notable observation is that in the autograph manuscript of the Iliad of the 12th c. [Laurenz. MS Plut. 59.03, f. 189v] the passage of text 20 and some lines before were added by Eustathius as a footnote at the end of the page. Cullhed [2012, p. 447] gives the dating of the Eustathius' works. He wrote firstly his comments in Iliad, then the ones of Odyssey. However, in Iliad he added some footnotes, as this one, written in a long period of time ahead, using new sources. And a strange coincidence occurs. In the knucklebone description in Iliad [rh.Ψ'/v.88, around text 20], Eustathius gives two pieces of information, not repeated in the relevant passage in Odyssey [rh.A'/v.107 around text 18], though the latter is bigger. Firstly the fact that the knucklebone game was played with four pieces of knucklebones [='τέσσαρσιν ἀστραγάλοις'], secondly a proverb by Kallimachus. Both these hints, along with the rest of the text, were given by Arethas in the 9th c. CE, as remarks in the Plato's dialogue Lysis, 206e; fact that can signify a possible origin of Eustathius' comments in Iliad [Bodl. Clarke MS 39, f. 308v & transcr. in Greene [1981], p. 456]. However, some other Byzantine remarks could be enlightening, too; indicating maybe a general view. For example the anonymous Plato's scholiast of the 9th c., commenting on Laws 7.820c, writes around petteia: "and pessoi are cubes [=dice]... and Aristarchus calls pessous the pieces with which they played..." [in BNF Grec 1807, 9th c. CE, f. 230r & transcr. in Greene [1981], p. 333]. Comment that probably underlines a possible misled identification between pessoi-pieces and dice, that could exist during those years in Byzantium, though Aristarchus' correct saying is also collated [possibly Aristarchus of Samothrace of the 3rd c. BCE]. Here also it could be applied Kidd's approach [2017b] but maybe in a wider way; meaning that the phrase 'pessoi are cubes' could be translated more freely as 'pessoi are gambling', but this with a huge doubt.

In any case this last text 20 seems irrational, or at least intentionally incomplete. Taking for granted what it's written, let's see what we have.: in a game played on a board with fields, the purpose is to eliminate opponent's pieces. This elimination, however, comes if I throw a dog, '1'. This 1 was the worst knucklebone throw, so what does it mean? That I should remove my own? But let's ignore this. If my prime goal is achieved by a throw and only, then why to play this game, and not just knucklebones? And what would happen if I never threw a dog? Best case scenario is that rules are omitted intentionally and that there were and other ways for capturing pieces. If that's the case, Eustathius is just giving the knucklebone version or part, without meaning that the game was played only with knucklebones [compare Schädler [2002], p. 97]. And this as a best case scenario.

Schädler was right. Eustathius does seem confused. Generally I believe that Eustathius' entries [texts 18 & 20] should be taken in account very cautiously.

5.2. Possible allusions of game Polis in petteia references since classical antiquity up

As we've seen in Cratinus' passage, mentioned by Pollux and Zenobius [texts 14 & 17], Polis was a known term in classical antiquity as a game. However polis also meant the city, the state. Texts have been tracked where petteia references and examples/comparisons are used on a discussion around the city/state. So an allusion of the game Polis is really probable.

5.2.1. Polis, a game of ruling virtue up

| Θησεύς: πρῶτον μὲν ἤρξω τοῦ λόγου ψευδῶς, ξένε, ζητῶν τύραννον ἐνθάδ· οὐ γὰρ ἄρχεται ἑνὸς πρὸς ἀνδρός, ἀλλ᾽ ἐλευθέρα πόλις. δῆμος δ᾽ ἀνάσσει διαδοχαῖσιν ἐν μέρει ἐνιαυσίαισιν, οὐχὶ τῷ πλούτῳ διδοὺς τὸ πλεῖστον, ἀλλὰ χὡ πένης ἔχων ἴσον. Κῆρυξ: ἓν μὲν τόδ᾽ ἡμῖν ὥσπερ ἐν πεσσοῖς δίδως κρεῖσσον: πόλις γὰρ ἧς ἐγὼ πάρειμ᾽ ἄπο ἑνὸς πρὸς ἀνδρός, οὐκ ὄχλῳ κρατύνεται· |

Theseus: Firsty you started your speech falsely, stranger, in seeking an absolute ruler here. As [this city] isn't ruled by one man, but is a free city. People rule it in succession every year, without giving the most to the wealth, but the poor have equal. Herald: You give us one advantage, as in a game of pessoi; as the city from which I come is ruled by one man only, not by the mob; |

A possible allusion of Polis game is obvious.

Euripides' Iketidai is a play written in 422 BCE ca. The plot till this scene, inspired from legend, has as follows: A battle for the control of the city of Thebes took place. Invaders lost, but both leaders died. Thebes' new leader ordered the non-burial of the enemies' dead bodies. Suppliant women from the city of Argos, that had sent troops against Thebes, ask from Theseus to intervene so to bury their beloved ones. However, he had to convince his Athenian co-citizens for this, as the city has democracy. Meanwhile a herald from Thebes arrives to Athens, so to ask from the city to keep neutrality.

So a comparison between monarchy and democracy is tried, using the game of pessoi with a probable allusion to the Polis one. Kurke [1999a, pp. 265-266] saw here a possible reference in two games, one corresponding to tyranny, one to democracy. More probable seems to me that the comparison between two political systems isn't transfered into a choice between two games. This as only the herald does mention pessoi. Theseus doesn't answer afterwards on this petteia reference. Instead, he calls the herald a good worker of the words, and starts analyzing directy the benefits of democracy.

Herald, right after considering that ruling by one man, instead of a mob, is an advantage, is explaining that not all men are able to rule a city, while many of the mob could be misled by words. If we apply these to the game, the meant advantage probably refers to the kind of the player, and not to the possible game rules. Seems more probable that the herald is implying here that ruling efficiently a city [polis] needs some quality, like playing in the game of Polis. An approach that agrees with Plato, in Politicos [Statesman], 292d-e [text 09].

5.2.2. City or cities? up

| - τί δ᾽ ἂν πρεσβείαν πέμψαντες εἰς τὴν ἑτέραν πόλιν τἀληθῆ εἴπωσιν, ὅτι ‘ἡμεῖς μὲν οὐδὲν χρυσίῳ οὐδ᾽ ἀργυρίῳ χρώμεθα, οὐδ᾽ ἡμῖν θέμις, ὑμῖν δέ· συμπολεμήσαντες οὖν μεθ᾽ ἡμῶν ἔχετε τὰ τῶν ἑτέρων;’ οἴει τινὰς ἀκούσαντας ταῦτα αἱρήσεσθαι κυσὶ πολεμεῖν στερεοῖς τε καὶ ἰσχνοῖς μᾶλλον ἢ μετὰ κυνῶν προβάτοις πίοσί τε καὶ ἁπαλοῖς; - οὔ μοι δοκεῖ. ἀλλ᾽ ἐὰν εἰς μίαν, ἔφη, πόλιν συναθροισθῇ τὰ τῶν ἄλλων χρήματα, ὅρα μὴ κίνδυνον φέρῃ τῇ μὴ πλουτούσῃ. - εὐδαίμων εἶ, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ὅτι οἴει ἄξιον εἶναι ἄλλην τινὰ προσειπεῖν πόλιν ἢ τὴν τοιαύτην οἵαν ἡμεῖς κατεσκευάζομεν. - ἀλλὰ τί μήν; ἔφη. - μειζόνως, ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, χρὴ προσαγορεύειν τὰς ἄλλας: ἑκάστη γὰρ αὐτῶν πόλεις εἰσὶ πάμπολλαι ἀλλ᾽ οὐ πόλις, τὸ τῶν παιζόντων. δύο μέν, κἂν ὁτιοῦν ᾖ, πολεμία ἀλλήλαις, ἡ μὲν πενήτων, ἡ δὲ πλουσίων· τούτων δ᾽ ἐν ἑκατέρᾳ πάνυ πολλαί, αἷς ἐὰν μὲν ὡς μιᾷ προσφέρῃ, παντὸς ἂν ἁμάρτοις, ἐὰν δὲ ὡς πολλαῖς, διδοὺς τὰ τῶν ἑτέρων τοῖς ἑτέροις χρήματά τε καὶ δυνάμεις ἢ καὶ αὐτούς, συμμάχοις μὲν ἀεὶ πολλοῖς χρήσῃ, πολεμίοις δ᾽ ὀλίγοις. καὶ ἕως ἂν ἡ πόλις σοι οἰκῇ σωφρόνως ὡς ἄρτι ἐτάχθη, μεγίστη ἔσται, οὐ τῷ εὐδοκιμεῖν λέγω, ἀλλ᾽ ὡς ἀληθῶς μεγίστη, καὶ ἐὰν μόνον ᾖ χιλίων τῶν προπολεμούντων· οὕτω γὰρ μεγάλην πόλιν μίαν οὐ ῥᾳδίως οὔτε ἐν Ἕλλησιν οὔτε ἐν βαρβάροις εὑρήσεις, δοκούσας δὲ πολλὰς καὶ πολλαπλασίας τῆς τηλικαύτης. |

- So what if they would send an embassy to the other city and tell the truth, that 'we don't use neither gold or silver, nor this is our law, but it's yours; so if you fight with us, you will get the [wealth] of the others;' you think that, after hearing these, they would prefer better to fight against dogs solid and thin or along with the dogs against sheep fat and tender? - I think not. But if the wealth of the others, he said, are accumulated in one city, look if there's danger for the non-wealthy [city]. - Fortunate you are, I said, thinking that some other [city] deserves to be called as a city, compared to the kind of the one that we are constructing. - But what [it should be called], he said. - The others, I said, should be called in a greater way [=plural]; cause each of them are many, and not one city, as the saying of the players goes. And two [cities they are; meant as components of a big one] at least, each fighing the other, the one of the poor, the other of the rich; and in each of them many [cities], which if you treated them as one, you would fail totally, but if [you treated them] as many, giving the wealth, powers or even persons, of the ones to the others, you would always have many friends [=allies], and few enemies. And till your city is governed prudently, like it was set above [=the one they were constructing], it will be the greatest, not in reputation I say, but truly the greatest, and even if it has only one thousand of defenders-fighters; cause you won't find easily one big city of this way neither in Greeks, nor in barbarians, but [you'll find] many and multiplied in size [cities] that seem [big]. |

The implication of the game Polis was so intense, that even the Plato's Scholiast of the 9th c. mentioned the game in his brief comments, and without a dice reference [BNF Grec 1807, f. 39r & transcr. in Greene [1981], p. 221].

Here Plato, is praising the city that shows unity and discipline compared with the one that has such diversity, that could be even considered as more cities in one. He argues that the former could prevail in war over the latter, even if the numbers were against. The transfer of this comparison to the game is easy. Just assume that the citizens are the pieces.

It's noticeable that here the word city [=πόλις] is close to the one for dogs [=κύνες], as its defenders-fighters; the name that Pollux had used for the game pieces. The term dogs had been used and at other instances of ancient Greek literature, out of game's references, to signify generally the guardian [eg. Aeschylus, Agamemnon 896] or even a god's agent [eg. Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 1022].

The difficulty of this text is the phrase 'τὸ τῶν παιζόντων', literally meaning 'the one of the players' making the allusion more intense. It's a phrase that has been tracked in Plato and in other excerpts, freely & safely translated: 'as they say (jestingly)'; and it's placed around possible proverbs [in Rep. 9.573d & Laws. 6.780c, but also see Laws 4.723ε]. However the mainstream approach, based and on the Scholiast of the 9th c., is that at least in this case, the game is implied too [check also Dobbs [2018], p. 69, Adam [1905], p. 211, in comments, contra Stewart [1893]].

5.2.3. The lonely piece - ἄζυξ up

| ἐκ τούτων οὖν φανερὸν ὅτι τῶν φύσει ἡ πόλις ἐστί, καὶ ὅτι ὁ ἄνθρωπος φύσει πολιτικὸν ζῷον, καὶ ὁ ἄπολις διὰ φύσιν καὶ οὐ διὰ τύχην ἤτοι φαῦλός ἐστιν, ἢ κρείττων ἢ ἄνθρωπος· ὥσπερ καὶ ὁ ὑφ᾽ Ὁμήρου λοιδορηθεὶς 'ἀφρήτωρ ἀθέμιστος ἀνέστιος'· ἅμα γὰρ φύσει τοιοῦτος καὶ πολέμου ἐπιθυμητής, ἅτε περ ἄζυξ ὢν ὥσπερ ἐν πεττοῖς. | So from these it's obvious that the city [=organized society/state] is of the natural [things] and that the man is by nature a political animal [=meant to live in organized society], and the citiless man by nature and not by fortune, is either lower or better than a man; just like the one who was reviled by Homer [as:] 'clanless, lawless, hearthless [=familyless, homeless]'; as he's by nature like this and at the same time desirous of war, just like being single [=without partner] just like in pettois. |

An important text of the 4th c. BCE. And a really difficult passage, that has caused many and different thoughts among the writers.

Aristotle considers that man is born meant to live in a society [in polis]. In case this doesn't occur cause of man's choice/nature, and not just accidentally, he considers man either lower or higher than the average human being. For this sets a poetic example taken from Homer, where a man actually out of the society is considered as 'desirous of war'. A strange expression, that connects it seemingly with an allegoric picture of a single piece [= 'ἄζυξ'] in some petteia game.

Footnoting: On the word ἄζυξ: It's a compound word. 1st component is the privative prefix 'α-', 2nd is the word 'ζυγός' with first translation as 'yoke'. So ἄζυξ is the unyoked, commonly used for a pair of animals that should drag a vehicle. And based on this it was meaning metaphorically the unpaired, the one without partner/match, the single; used for example for the unmarried or even the virgin. However one of the early translations of 'ζυγός' was also the rank, file, of a troop formation. And made me wonder if this ἄζυξ here would have also the meaning of the one out of this formation. Really wide approach. In any case the translation as 'single' or better 'unpaired' are sufficient enough.

The mention of the word polis [=city] along with the relevant meanings gave a strong argument for supporting a connection with the game Polis described by Pollux [Austin [1940]]. Such a connection could even be a justification of Pollux's description of capturing [text 14], where two pieces prevail over one; this as ἄζυξ [=azyx] means the unpaired. And it's one strong enough coincidence that in the Roman Ludus Latrunculorum, the enemy that could capture a piece was called on the contrary 'twin' or 'two-headed' [under B.2.4.].

But the word ἄζυξ had been also tracked in a poem of Agathias Scholasticus, of the 6th c. CE, describing a backgammon-like game, where this single piece seemed to be a 'blot', a piece that can be hit during the game; regarding the Aristotle's time, possibly the Pente Grammai would be meant [from the latest and really enriched Kidd [2017a], also Susemihl & Hicks [1894], p. 148].

However a general sceptisism has been expressed already since 19th c. [Newman [1887], p. 121, Jackson [1877]]; and Thraede in 1967 just considers it a poetic addition having speech-metrical characteristics. Hubner [2009] seems rejecting, or at least arguing against, both possible connections with the specific games of petteia. Regarding the backgammon-like one of Agathias, mostly cause of the really long time that separates the two texts, almost 1.000 years, without the existence of any other intermediate written record that would mention the term. The fact that also Pollux doesn't cite the word, though he was quoting terms even without explanation, agrees with Hubner's argument. Regarding the possibility of Polis, Hubner rejects it mainly with the thought that a single piece can't be considered as 'desirous of war', while it can be captured by two of the opponent's, not being itself able to attack. He seems partially concluding that game comparisons were usual in ancient texts, and we shouldn't take them to the letter.

But I think that this 'desirous of war' may give the solution. Before analyzing it, two preconditions:

i. Aristotle's text is a philosphical/political one, not poetic. In the relevant petteia allegory the particle '-περ' is used, literally meaning just->very much/exactly, signifying the accuracy of the comparison. And in fact this word can be seen twice. Aristotle seems to feel sure for this allegory.

ii. Ancient Greeks were quite familiar with the Homeric epics. These were the most famous work for centuries by far and part of their entairtainment. To such degree, that it was said that Solon the Athenian, legislator of the 6th c. BCE, had issued decree ordering the bards of the Homeric epics to recite them in sequence when in public; meaning each would continue from the point that the last stopped; and this according to law. Fact that underlines the position of these works in the life of the ancient Greeks. So when Aristotle is referring to Homer in this passage, he's probably addressing to an aware audience.

Already since 1877 Jackson had noted that the Homeric passage should be seen complete so to understand Aristotle. And he was right on this.

| ἀφρήτωρ ἀθέμιστος ἀνέστιός ἐστιν ἐκεῖνος, ὃς πολέμου ἔραται ἐπιδημίου ὀκρυόεντος. | clanless, lawless, hearthless [=familyless, homeless] is he, who loves the chilling [=horrible] civil war. |

So that 'desirous of war' is based on Homer and it's in fact a 'civil war'. To understand what Homer was saying let's see the plot. The Achaeans were losing by the Trojans, so badly that their leader Agamemnon suggested quiting the war. Reaction followed in the camp. And the above were of the words told by Nestor, of the elders and wisests. He was trying to forestall some possible reaction in a conference that would follow, where Nestor was planning to propose to Agamemnon a delegation to the mighty warrior Achilles. Achilles, the best Achaean warrior, was refusing to fight, cause of a dispute he had with Agamemnon. So Nestor was actually suggesting that an apology should be asked with ultimate goal Achilles to join again the war against the Trojans. And Agamemnon was convinced.

Hence this civil 'war' wasn't even a war, but a possible dispute, a verbal conflict, between leading men of the same side. At a first level the obvious is meant: a conflict between the side that would do anything to continue the war and the one that would quit. But at a second level, it should be at least implied the dispute between Achilles and Agamemnon, of the main elements of Iliad. And I don't know if it's a poetic irony or just a word-toying, but the use of the word 'πολέμου' [='war'] in Homer creates here a verbal-meaning contrast; the mighty warrior Achilles, actually is refusing to fight and join the Trojan war, cause of the previous dispute [='civil war'] he had with Agamemnon. So the emphasis in this phrase is transfered on the word ἐπιδημίου [=civil].

Aristotle doesn't need to repeat the whole Homer's words; and the sentence's structure was altered, changing places between subject & predicate. While in Homer the civil war lover is a clanless man, in Aristotle the citiless is a desirous for war; probably a change for emphasis, as he's speaking to an aware audience. And Aristotle's lines are making sense now. The citiless man is one who desires a dispute/disruption inside his own [previous] city.

Transfering these to a possible game of petteia, the single piece [ἄζυξ] is a piece that would cause problems, disruption, to its own side. And this piece seems to be something exceptional, not the rule, just like the case in Iliad. A known to the auditors game strategy is probably implied here; pieces should be united and close to each other.

These could be understood easily for an open-boarded, draught-like game; a backgammon-like one doesn't seem that possible. Τhere the 'blots' are almost a necessity in the gameplay and would occur by force cause of the dice-throws. They would just cause a delay, as more possibly the struck piece would start the race again or just wait till it would be free again [according to the possible backgammon rules as we know them today]. Something common, maybe no big deal. And in any case if here this backgammon-type game would be played with only five stones, just like Pente Grammai, a blot is not just a necessity but almost the only real thing, cause of the small number of the pieces.

Further this caused disruption in one's camp cause of a single piece feels a little irrational, if it's applied in a backgammon-like game. It would just start the race again. In an open boarded one, where less pieces would mean gradually less power, makes more sense; and it would be mainly the player's choice either to isolate a piece or to attack with two or more pieces. If that's the case, pieces' moves shouldn't also be that free and powerful, meaning not a rook-like one; as then the single pieces could be supported easily or flee, and they wouldn't be such a problem.

With these in mind, if I had to choose between Pollux's Polis or Pente Grammai, I would choose Polis.

Footnoting: I was curious enough to search for the manuscript tradition of this Aristotle's passage, and I've managed to find 8 manuscripts. A strange, and noted generally by writers, thing is that in five here manuscripts [d, e, f, g, h] the word ἄζυξ is omitted, but leaving a gap at its possible place. Like the transcriber avoided to write it, cause maybe he couldn't read it or recognize it. From the rest three, two [b, c] have the text as above, but with a scholion/remark of the word πετεινοῖς [peteinois], that literally means 'birds/able to fly', as explanation of the word πεττοῖς [pettois, the game]. The latter seems with a little doubt that has to do with the first latin translations of text in the 13th c. by William of Moerbeke, where the relevant Aristotle's game expression was given as a free-lonely birds, instead of single piece. Possibly mistransliteration but not sure [for English translation of the Latin text, check Regan [2007]]. There's no doubt among the writers that the correct Greek text has the game as comparison. The manuscript (a) has the correct text as given here, without remarks, which seems to be the oldest of all these. The manuscripts: (a) BNF Coislin MS 161, 14th c., f. 168v / (b) BNF Grec MS 2025, 15th c., f. 2v / (c) BNF Grec MS 2023, 15th c., f. 117r / (d) BNF Grec MS 1857, 1492 CE, f. 3v / (e) BNF Grec MS 2026, 15th c., f. 3r / (f) BL Harley MS 6874, 15th c., f. 2r / (g) LOC Greek MS 2124, 15th c., f. 26r / (h) VAT Barb. gr. 215, 15th c., f. 2r

5.2.4. Mixed up pieces, an ugly picture up

| ἐγὼ δὲ δώσω τὴν ἐμὴν παῖδα κτανεῖν. λογίζομαι δὲ πολλά· πρῶτα μὲν πόλιν οὐκ ἄν τιν᾽ ἄλλην τῆσδε βελτίω λαβεῖν· ᾗ πρῶτα μὲν λεὼς οὐκ ἐπακτὸς ἄλλοθεν, αὐτόχθονες δ᾽ ἔφυμεν· αἱ δ᾽ ἄλλαι πόλεις πεσσῶν ὁμοίαις διαφοραῖς ἐκτισμέναι ἄλλαι παρ᾽ ἄλλων εἰσὶν εἰσαγώγιμοι. | And I will give my daughter to be killed. And I think of many; firstly that one can't have a better city than this [=Athens]; where firstly people aren't brought in from elsewhere, indigenous [=natives] we were born; and the other cities are built by moves similar [to ones] of the game-pieces, others are imported from others [<-probably colonies meant]. |

This is a fragment from a lost now tragedy of Euripides, called Erechtheus, the mythical first king of ancient Athens. According to this legend, at the time of Erechtheus, Athens was about to be attacked by the Thracians, and the Athenian king went to the oracle of Delphoi asking for a prophecy. He was said that he should sacrifice his own daughter. The passage is part of the acceptance of the prophecy by Praxithea, the girl's mother, praising actually the city of Athens. It's a text of the 5th c. BCE that was used & found in a rhetoric speech by Lycourgos in 332 BCE ca.

The general meaning is easy to understand but an exact translation is really difficult as the work is poetic. However, the main line that interests us isn't that hard. Trying to describe the cities that aren't constituted by native citizens, says that they are 'built by moves similar [to ones] of the game-pieces'. Putting aside the obvious xenophobia, this is said describing something unwanted compared to homogeneity of Athens. And regarding the petteia-Polis game, the only picture that could come up is one on an open board with pieces trying to constitute a city but being mixed up in color, as a mosaic.

A similar fragment of this tragedy is given by Plutarch, some centuries later. Of the following four lines, three are identical with the previously given and one slightly altered. The rest of the whole passage, not given here, is different; and by this it can be concluded that isn't just a different tradition of the same text, but a repetion of some lines, slightly altered, belonging to a different passage of a tragedy, possibly as a response.

| ᾗ πρῶτα μὲν λεὼς οὐκ ἐπακτὸς ἄλλοθεν, αὐτόχθονες δ᾽ ἔφυμεν· αἱ δ᾽ ἄλλαι πόλεις πεσσῶν ὁμοίως διαφορηθεῖσαι βολαῖς, ἄλλαι παρ᾽ ἄλλων εἰσὶν εἰσαγώγιμοι. | ... where firstly people isn't brought in from elsewhere, indigenous [=natives] we were born; and the other cities are scattered [torn in pieces, disrupted] with strikes [or throws] like of game-pieces, others are imported from others [<-probably colonies meant]. |

Plutarch gave it as an example of contradiction; explaining that the one who wrote these lines, Euripides, actually died away from Athens, in the court of the Macedonian king, Archelaus.