The Ruy Lopez with Black (in the hands of the Great Masters), Part I

The inspiration for this blog started by observing a common theme between Zukertort and Alexandra Kosteniuk, mainly in the Closed Ruy, when White decides to attack with a pawn storm on the Kingside, gaining space with g4. In these two games, Zukertort and Kosteniuk both devised a counterattack based on the move h5, and the subsequent opening of lines in Black's favor!

This led to exploring some of the games by the Old Masters, such as Chigorin, Rubinstein, Zuklertort, Lasker and Schlechter, all of which played the Ruy Lopez excellently with Black. In particular, Chigorin's system with Nf6-d7 in the Steinitz Defense (an idea which later became known as the "Keres Variation") was highly sucessful, gaining the praise of none other than Tarrasch, even though Chigorin's idea meant Black would have a "ruined" pawn structure on the queenside, with Black pawns on a6, c7, c6 and d6....

This kind of structure gave Black the open b-file for his rooks, as well as the two bishops (when White exchanged on c6), and inspired players like Bronstein and Larsen, among others, who showed the viability of such structures for Black.

The first game is Munk-Zukertort, which I have already published in another blog....

The second game is Hou Yifan-Kosteniuk, from their World Championship Match:

The following Rubinstein game against Alapin is illustrative of Rubinstein's defensive plan in the Chigorin variation....the f6 Knight retreats to e8, followed by g6, f6, Ng7 and Nf7, covering the possible invasion points in Black's formation:

In the following game, played 18 years after the Alapin game, Rubinstein plays his system again....and proceeds to outplay his opponent:

We move now to examine a sampling of the games of the Old Masters....and we start with Chigorin, a great pioneer in modern chess!

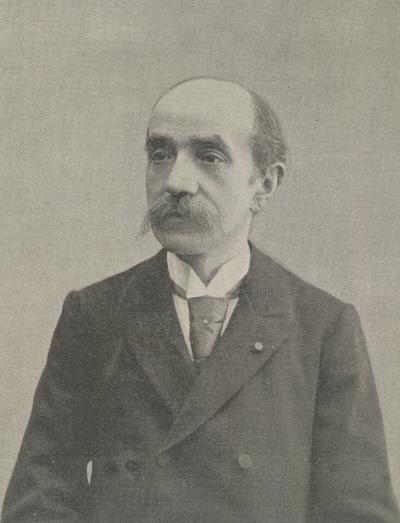

Mikhail Chigorin (1850-1908)

In the following game, from 1878, White tries to restrict Black's options by exchanging his bishop on c6 for Black's knight, but playing a slow system with d3...Chigorin fianchettoes his bishop on g7 and, together with his pawn majority in the centre and the two bishops, proceeds to open the game and gain the advantage. Chigorin shows the overall faults in White's idea. Let us see:

| Chigorin - Tarrasch (1893) |

|

This match was contested in St. Petersburg, Russia between October 8 and November 14, 1893. (1) The time control was 15 moves an hour, and the stakes were 5,000 marks per side. (1) The first player to win ten games would win the match, but if each player won nine games, the match would end without a winner. (1) In Dreihundert Schachpartien, Tarrasch wrote that he received an invitation "couched in the most flattering terms" from St. Petersburg. (1) On the other hand, Garry Kasparov stated in his On My Great Predecessors, Part I that Tarrasch challenged Chigorin. (2) In any case, the German arrived in St. Petersburg on October 4 and the match began four days later. (3) Photo: http://www.encspb.ru/image/28039904. St. Petersburg, 8 October - 14 November 1893

Chigorin 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 ½ 0 ½ ½ 0 1 ½ 0 1 1 1 0 1 11 Tarrasch 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 ½ 1 ½ ½ 1 0 ½ 1 0 0 0 1 0 11 Tarrasch never trailed, winning the first game in 29 moves, later leading 4-2, but he couldn't shake Chigorin. After 17 games, Tarrasch led +8 -5 =4, and wrote that everyone thought (me most of all) that the match was decided in my favor. (3) But Chigorin promptly won three in a row to tie the match again. Tarrasch won the 21st game, but Chigorin took the 22nd in a fascinating endgame. Thus, under the rules, the match ended in a tie: +9 -9 =4.Kasparov praised the match for the richness of its chess content and noted that the contestants "fought literally to the to the last pawn: in the first nine games and the six final ones there was not a single draw!" (2) The match is also prized because of its clash of styles. Tarrasch was an exponent of classical chess. Kasparov wrote that "Both in his play, and in his commentaries, Tarrasch aimed to follow general rules, and he methodically formulated them". (4) Chigorin was different. As Mikhail Botvinnik put it, "To get any idea of Tchigorin’s creative style we must realize that he frequently looked not for the rules but the exceptions". (5) The Russian repeatedly adopted 2.Qe2 against Tarrasch's French Defense, leading in a number of cases to the sort of King's Indian Reversed that would become popular in the following century. Contemporary reaction: "All chess-players will to learn that, without any preliminary trumpeting, a match has been arranged to take place at the St. Petersburg Chess Club between Mr. Tschigorin and Dr. Tarrasch. Five games a week will be played, and the winner will be the one who scores ten first, draws not counting. The contest will be the more attractive as it will form some guide to the chance Dr. Tarrasch would have in match with Mr. Steinitz. The former is undoubtedly a champion of the first rank, but great tournament skill is not always reflected in match play, and in at least one notable instance it almost disappears. The style of Dr. Tarrasch, however, makes it probable he is as good at one thing as the other, and Mr. Tschigorin will have to do his best — great as it is — to beat him." (6) A COMING CHESS MATCH. Reuter's telegram. ST. PETERSBURG, Sept. 10. A great international chess match is to take place at the St. Petersburg Chess Club in the course of next week. The competitors are M. Tschigorin, the famous Russian player, and Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch, who has taken part in all the principal chess tournaments of the past few years. He won distinction in England while playing at Manchester in 1890. The stake in the forthcoming match is 5,000 marks a side (£250), and the prize will be awarded to the player who first wins 10 games, drawn games not being counted. MM. Tschigorin and Tarrasch will play five days a week, one game being finished each day. (7) The great Chess Match at St. Petersburg has ended in a draw — a fitting termination to so determined a contest. According to the conditions the first winner of ten games was to be the victor, but it was judiciously provided that in the un- likely event of the score becoming "nine all" the match should be drawn. This circumstance, which, though provided for, was certainly never expected, has now occurred, and by the fortunate provision referred to we are spared the spectacle of an important and hardly-fought encounter being decided by the chances of a single game when both players are doubtless wearied by their protracted efforts. Under such circumstances they could not appear at their best, and if the contest had been fought out to the bitter end it would have resulted in an inconclusive victory for the competitor who happened to display the greater physical endurance and nerve. The conclusion, however, is not the only remarkable feature of the match, which was not alone a trial of strength be- tween two individual experts, but, what was per- haps more important, a struggle for supremacy between the old and the new schools of chess. Dr. Tarrasch is certainly the leading European exponent of the "modern school" initiated by Steinitz, which is based on the theory that the steady accumulation of minor advantages, such as the odd Pawn on the Queen's side, is a more certain road to victory than that achieved by the dashing coups which used to delight Anderssen, Labourdonnais, and the players of a former generation. Impetuous attacks carry with them the danger of disastrous retreats, and, though sometimes successful, they cannot be relied upon with any degree of certainty. Thus, while Tarrasch relies on the slow and sure modern tactics, Tschigorin enjoys the well- earned reputation of being the most skilful and vigorous of modern players as regards his capacity for attack, though he is far from reliable in complicated requiring delicate defensive manoeuvres. Tschigorin, indeed, may be said to carry on the traditions of the old school more thoroughly than any other player, unless it be the veteran Englishman Mr. Bird. But recent „experience seemed to show that tactics which were good enough in the old days, when men were not anxious to analyse chess so microscopically as now, could not be adopted with success in modern competitions. Tschigorin it is true, has an advantage over his predecessors, inasmuch as all the work of the analysts is at his disposal; but being an original and imaginative player his tendency is, naturally to discard booklore and to trust to his own resources. These considerationscombied with Tarrasch's unbeaten record, no doubt accounts for the general anticipation of an easy victory for the German amateur. This anticipation was strengthened by the first few games, notwithstanding one or two dashing victories by Tschigorin. It was thought that Tarrasch only lost by accident and that he held his opponent well in hand all the same. Tschigorin, too, was driven to adopt an unfavourable variation in the French Defence in order to avoid the book knowledge of his rival. But notwithstanding this, the victories of the Russian, became more frequent, until at last he caught his adversary's score just in time to make the match a tie. The members of the St. Petersburg Chess Club are to be congratulated on their enterprise in bringing about the match, which has not only produced exceptionally fine examples of chess, but has resulted in a vindication of the methods of old school, which will probably do much to restore it to popularity. The undeniable dullness of recent tournaments has been chiefly due to the adoption of "modern" theories, and if players are encouraged in future to exercise their imagination more freely they will introduce a welcome relief. (8) Sources 1) Tarrasch, Siegbert. "Dreihundert Schachpartien" (Von Veit & Co., Leipzig, 1895), pp. 419, 496. Available on Google Books at https://books.google.no/books/about. and https://books.google.no/books/about. 2) Kasparov, Garry. "On My Great Predecessors Part I" (Everyman Publishers, 2003), p. 89. 3) DS, p. 420. 4) OMGP I, p. 150. 5) Mikhail Botvinnik, "100 Selected Games" (Dover, 1960), p. 211. 6) Illustrated London News - Saturday 30 September 1893, p.23. 7) Morning Post - Thursday 21 September 1893, p.5 8) Morning Post - Friday 17 November 1893, p.4. |

(This information was taken from chessgames.com)

This game was the 3rd game of the match. Chigorin plays an original idea (5....Nd7) in the Ruy Lopez. This is one of Chigorin's many contributions to opening theory, and is the foundation of what later became Keres' Variation in the Chigorin Ruy Lopez! Let us take a look!

The following game was played in Nuremberg, in 1896, and the word that comes to my mind when I play over the moves of this game is: "Perfect!"

Even though this game is a Ruy Lopez, it ends up looking like a Benoni, with Black pawns on e5, d6 and c5! Chigorin establishes total dominance over the dark squares!

Emil Schallopp

(1843-1919)

In the following game, Winawer loses his way in the complications, after Zukertort

makes a mistake which would have given Winawer the advantage!

In the following game, played in 1881, Zukertort invites his opponent to attack on the kingside, all the while knowing that his own pieces are ideally placed for defence, and also controlling key squares in the centre.

Looking at the moves of the following game, I became aware of the fact that Zukertort was playing exceptionally well, one can say that he played inspired! So Iooked up the results of the London 1883 tournament, and of course, Zukertort won it by a wide margin!

"The tournament was a runaway success for Zukertort. In the first twenty-three rounds his score was an astounding (+22 -1 =0)! However, the length and strain of the tournament took its toll on Zukertort and he used opium during the final three rounds to help himself relax, which would contribute to his losses in those games. James Mason held second place at the end of the first cycle of games, but would eventually fall to shared fifth with George Mackenzie and Berthold Englisch. He was replaced at second for the tournament final by Steinitz, followed by Blackburne at third employing a more solid approach, with Mikhail Chigorin taking fourth place. Though Steinitz crushed the weaker opposition, his unusual style of play that had won him Vienna (1882), proved inconsistent against the top players here and failed to secure him enough wins to challenge Zukertort for first. Samuel Rosenthal, another strong master who had contested a match with Zukertort three years earlier, fell victim to the tournament's draw policy. He was forced to replay a majority of his games, earning twenty-six decisive results, but through playing 45 games total over 59 days. His one consolation was a brilliancy prize he won for defeating Steinitz in a replayed game. During the prize ceremony at the end of the tournament, a toast was made to the best player in the world. Steinitz, who was crippled at the time, struggled to rise, but Zukertort was already standing and accepting the accolades. A red-faced Steinitz remained in his seat and was forced to endure the applause. Steinitz would prove the better player in his match with Zukertort three years later, a match which would be heralded as the first official world championship of chess. The fact remains, however, that Zukertort was seen by many at the time of this tournament as the best player in the world and some historians even regard the tournament itself as an unofficial world championship in the tradition of London (1851) and London (1862)." quoted from chessgames.com-

The next game is a positional masterpiece, a real work of Chess Art. We can only witness the greatness of the concept, the continuity of the idea, until we see the advantage materialise in a pawn ending!

Berthold Englisch

(1851-1897)

"Berthold Englisch (9 July 1851, Osoblaha – 19 October 1897, Vienna) was a leading Austrian chess master.

Englisch was born in Czech Silesia (then Austria-Hungary) into a Jewish family. He earned his living as a stock-market agent.

He won the tournaments at Leipzig 1879 (the 1st DSB Congress), at Wiesbaden 1880 (ex-equo with Blackburne and A. Schwarz, ahead of Schallopp, Mason, Bird, Winawer, etc.) and at Vienna 1896 (Quadrangular).[1]

He lost two matches against Vincenz Hruby in 1882 and to Emanuel Lasker in 1890, both scoring 1.5 : 3.5, and drew a match with Harry Nelson Pillsbury 2.5 : 2.5 (+0 –0 =5) in 1896, all in Vienna."

two giants of the game- Tarrasch and Lasker!

(1862-1934)

Tarrasch-Lasker

Berlin, 1918

In the following game, Zukertort (Black) outplays his opponent in positional understanding....

Johannes Metger

(1851-1926)

We move now to one of the greatest players to ever play the game, if not the greatest: Emmanuel Lasker!

Emmanuel Lasker

(1868-1941)

Emanuel Lasker was the second official World Chess Champion, reigning for a record 27 years after he defeated the first World Champion, Wilhelm Steinitz, in 1894.

Statistician Jeff Sonas of Chessmetrics writes, "if you look across players' entire careers, there is a significant amount of statistical evidence to support the claim that Emanuel Lasker was, in fact, the most dominant player of all time." http://en.chessbase.com/post/the-gr. By Sonas' reckoning, Lasker was the No. 1 player in the world for a total of 24.3 years between 1890 and 1926.

Background

He was born (on the same date as Richard Teichmann) in what was then Berlinchen (literally "little Berlin") in Prussia, and which is now Barlinek in Poland. In 1880, he went to school in Berlin, where he lived with his older brother Berthold Lasker, who was studying medicine, and who taught him how to play chess. By Chessmetrics' analysis, Berthold was one of the world's top ten players in the early 1890s.

Tournaments

Soon after Lasker obtained his abitur in Landsberg an der Warthe, now a Polish town named Gorzow Wielkopolski, the teenager's first tournament success came when he won the Café Kaiserhof's annual Winter tournament 1888/89, winning all 20 games. Soon afterwards, he tied with Emil von Feyerfeil with 12/15 (+11 -2 =2) at the second division tournament of the sixth DSB Congress in Breslau, defeating von Feyerfeil in the one game play-off.* Also in 1889, he came second with 6/8 (+5 -1 =2) behind Amos Burn at the Amsterdam "A" (stronger) tournament, ahead of James Mason and Isidor Gunsberg, two of the strongest players of that time. In 1890 he finished third in Graz behind Gyula Makovetz and Johann Hermann Bauer, then shared first prize with his brother Berthold in a tournament in Berlin. In spring 1892, he won two tournaments in London, the second and stronger of these without losing a game. At New York 1893, he won all thirteen games, one of a small number of significant tournaments in history in which a player achieved a perfect score. Wikipedia article: List of world records in chess#Perfect tournament and match scores

After Lasker won the title, he answered his critics who considered that the title match was by an unproven player against an aging champion by being on the leader board in every tournament before World War I, including wins at St Petersburg in 1895-96, Nurenberg 1896, London 1899, Paris 1900 ahead of Harry Nelson Pillsbury (by two points with a score of +14 −1 =1), Trenton Falls 1906, and St Petersburg in 1914. He also came 3rd at Hastings 1895 (this relatively poor result possibly occurring during convalescence after nearly dying from typhoid fever), 2nd at Cambridge Springs in 1904, and =1st at the Chigorin Memorial tournament in St Petersburg in 1909. In 1918, a few months after the war, Lasker won a quadrangular tournament in Berlin against Akiba Rubinstein, Carl Schlechter and Siegbert Tarrasch.

After he lost the title in 1921, Lasker remained in the top rank of players, winning at Maehrisch-Ostrau (1923) ahead of Richard Reti, Ernst Gruenfeld, Alexey Sergeevich Selezniev, Savielly Tartakower, and Max Euwe. His last tournament win was at New York 1924, where he scored 80% and finished 1.5 points ahead of Jose Raul Capablanca, followed by Alexander Alekhine and Frank James Marshall. In 1925, he came 2nd at Moscow behind Efim Bogoljubov and ahead of Capablanca, Marshall, Tartakower, and Carlos Torre Repetto. There followed a long hiatus from chess caused by his intention to retire from the game, but he re-emerged in top-class chess in 1934, placing 5th in Zurich behind Alekhine, Euwe, Salomon Flohr and Bogoljubow and ahead of Ossip Bernstein, Aron Nimzowitsch, and Gideon Stahlberg. In Moscow in 1935, Lasker finished in an undefeated third place, a half point behind Mikhail Botvinnik and Flohr and ahead of Capablanca, Rudolf Spielmann, Ilia Abramovich Kan, Grigory Levenfish, Andre Lilienthal, and Viacheslav Ragozin. Reuben Fine hailed the 66-year-old Lasker's performance as "a biological miracle". In 1936, Lasker placed 6th in Moscow and finished his career later that year at Nottingham when he came =7th with 8.5/14 (+6 -3 =5), his last-round game being the following stylish win: Lasker vs C H Alexander, 1936.

Matches

Non-title matches 1889 saw his long career in match play commence, one which only ceased upon relinquishing his title in 1921. He won nearly of his matches, apart from a few drawn mini-matches, including a drawn one-game play-off match against his brother Berthold in Berlin in 1890, losing only exhibition matches with Mikhail Chigorin, Carl Schlechter and Marshall, and a knight-odds match against Nellie Showalter, Jackson Showalter's wife. In 1889, he defeated Curt von Bardeleben (+1 =2) and in 1889-90 he beat Jacques Mieses (+5 =3). In 1890, he defeated Henry Edward Bird (+7 -2 =3) and Nicholas Theodore Miniati (+3 =2 -0), and in 1891 he beat Francis Joseph Lee (+1 =1) and Berthold Englisch (+2 =3). 1892 and 1893 saw Lasker getting into his stride into the lead up to his title match with Steinitz, beating Bird a second time (5-0) Lasker - Bird (1892) , Joseph Henry Blackburne (+6 =4), Jackson Whipps Showalter (+6 -2 =2) and Celso Golmayo Zupide (+2 =1). In 1892, Lasker toured and played a series of mini-matches against leading players in the Manhattan, Brooklyn and Franklin Chess Clubs. At the Manhattan Chess Club, he played a series of three-game matches, defeating James Moore Hanham, Gustave Simonson, David Graham Baird, Charles B Isaacson, Albert Hodges, Eugene Delmar, John S Ryan and John Washington Baird of the 24 games he played against these players he won 21, losing one to Hodges and drawing one each with Simonson and Delmar. At the Brooklyn Chess Club, Lasker played two mini-matches of two games each, winning each game against Abel Edward Blackmar and William M De Visser, and drew the first game of an unfinished match against Philip Richardson. Lasker finished 1892 at the Franklin Chess Club by playing 5 mini-matches of two games each against its leading players, winning every game against Dionisio M Martinez, Alfred K Robinson, Gustavus Charles Reichhelm and Hermann G Voigt and drawing a match (+1 -1) with Walter Penn Shipley. Shipley offered cash bonuses if he could stipulate the openings and taking up the challenge, Lasker played the Two Knight's Defense and won in 38 moves, while in the second game, Shipley won as Black in 24 moves against Lasker playing the White end of a Vienna Gambit, Steinitz variation (Opening Explorer). Shipley, who counted both Lasker and Steinitz as his friends, was instrumental in arranging the Philadelphia leg of the Lasker-Steinitz match, that being games 9, 10 and 11. 29 years later, Shipley was also the referee of Lasker’s title match with Capablanca. In 1892-3, Lasker also played and won some other matches against lesser players including Andres Clemente Vazquez (3-0), A Ponce (first name Albert) (2-0) and Alfred K Ettlinger (5-0). Also in 1893, Mrs. Nellie Showalter, wife of Jackson Showalter and one of the leading women players in the USA, defeated Lasker 5-2 in a match receiving Knight odds.

These matches pushed Lasker to the forefront of chess, and after being refused a match by Tarrasch, he defeated Steinitz for the world title in 1894 after spreadeagling the field at New York 1893. While he was World Champion, Lasker played some non-title matches, the earliest of which was a six-game exhibition match against Chigorin in 1903 which he lost 2.5-3.5 (+1 -2 =3); the match was intended as a rigorous test of the Rice Gambit, which was the stipulated opening in each game. In the midst of his four title defenses that were held between 1907 and 1910, Lasker played and won what appears to have been a short training match against Abraham Speijer (+2 =1) in 1908. Also in 1908, he played another Rice Gambit-testing match, this time against Schlechter, again losing, this time by 1-4 (+0 =2 -3), apparently prompting a rethink of the Rice Gambit as a viable weapon.** In 1909 he drew a short match (2 wins 2 losses) against David Janowski and several months later they played a longer match that Lasker easily won (7 wins, 2 draws, 1 loss). Lasker accepted a return match and they played a title match in 1910 (details below). In 1914, he drew a 2 game exhibition match against Bernstein (+1 -1) and in 1916, he defeated Tarrasch in another, clearly non-title, match by 5.5-0.5. After Lasker lost his title in 1921, he is not known to have played another match until he lost a two-game exhibition match (=1 -1) against Marshall in 1940, a few months before he died. A match between Dr. Lasker and Dr. Vidmar had been planned for 1925, but it did not eventuate.***

World Championship matches The Lasker - Steinitz World Championship (1894) was played in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. Lasker won with 10 wins, 5 losses and 4 draws. Lasker also won the Lasker - Steinitz World Championship Rematch (1896), played in Moscow, with 10 wins, 2 losses, and 5 draws. At one stage when Rudolf Rezso Charousek ‘s star was in the ascendant, Lasker was convinced he would eventually play a title match with the Hungarian master; unfortunately, Charousek died from tuberculosis in 1900, aged 26, before this could happen. As it turned out, he did not play another World Championship for 11 years until the Lasker - Marshall World Championship Match (1907), which was played in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, Chicago, Memphis. Lasker won this easily, remaining undefeated with 8 wins and 7 draws.

After a prolonged period of somewhat strained relations due to Tarrasch’s refusal of Lasker’s offer for a match, Lasker accepted Tarrasch’s challenge for the title, and the Lasker - Tarrasch World Championship Match (1908) was played in Düsseldorf and Munich, with Lasker winning with 8 wins 3 losses and five draws. In 1910, Lasker came close to losing his title when he was trailing by a full point at the tenth and last game of the Lasker - Schlechter World Championship Match (1910) (the match being played in Vienna and Berlin); Schlechter held the advantage and could have drawn the game with ease on several occasions, however, he pursued a win, ultimately blundering a Queen endgame to relinquish his match lead and allow Lasker to retain the title. Some months later, the Lasker - Janowski World Championship Match (1910) - played in Berlin - was Lasker’s final successful defense of his title, winning with 8 wins and 3 draws.

In 1912 Lasker and Rubinstein, agreed to play a World Championship match in the fall of 1914 but the match was cancelled when World War I broke out. The war delayed all further title match negotiations until Lasker finally relinquished his title upon resigning from the Lasker - Capablanca World Championship Match (1921) in Havana while trailing by four games.

Life, legacy and testimonials

Lasker’s extended absences from chess were due to his pursuit of other activities, including mathematics and philosophy. He spent the last years of the 19th century writing his doctorate. Between 1902 and 1907, he played only at Cambridge Springs, using his time in the US. It was during this period that he introduced the notion of a primary ideal, which corresponds to an irreducible variety and plays a role similar to prime powers in the prime decomposition of an integer. He proved the primary decomposition theorem for an ideal of a polynomial ring in terms of primary ideals in a paper Zur Theorie der Moduln und Ideale published in volume 60 of Mathematische Annalen in 1905. A commutative ring R is now called a 'Lasker ring' if every ideal of R can be represented as an intersection of a finite number of primary ideals. Lasker's results on the decomposition of ideals into primary ideals was the foundation on which Emmy Noether built an abstract theory which developed ring theory into a major mathematical topic and provided the foundations of modern algebraic geometry. Noether's Idealtheorie in Ringbereichen (1921) was of fundamental importance in the development of modern algebra, generalising Lasker's results by giving the decomposition of ideals into intersections of primary ideals in any commutative ring with ascending chain condition.****

After Lasker lost his title, he spent a considerable amount of time playing bridge and intended to retire. However, he returned to chess in the mid-thirties as he needed to raise money after the Nazis had confiscated his properties and life savings. After the tournament in Moscow in 1936, the Laskers were encouraged to stay on and Emanuel accepted an invitation to become a member of the Moscow Academy of Science to pursue his mathematical studies, with both he and his wife, Martha, taking up permanent residence in Moscow. At this time, he also renounced his German citizenship and took on Soviet citizenship. Although Stalin's purges prompted the Laskers to migrate to the USA in 1937, it is unclear whether they ever renounced their Soviet citizenship.

Lasker was friends with Albert Einstein who wrote the introduction to the posthumous biography Emanuel Lasker, The Life of a Chess Master by Dr. Jacques Hannak (1952), writing: Emanuel Lasker was undoubtedly one of the most interesting people I came to know in my later years. We must be thankful to those who have penned the story of his life for this and succeeding generations. For there are few men who have had a warm interest in all the great human problems and at the same time kept their personality so uniquely independent.

Lasker published several chess books but as he was also a mathematician, games theorist, philosopher and even playwright, he published books in all these fields, except for the play which was performed on only one occasion. As a youth, his parents had recognised his potential and sent him to study in Berlin where he first learned to play serious chess. After he graduated from high school, he studied mathematics and philosophy at the universities in Berlin, Göttingen and Heidelberg. Lasker died in the Mount Sinai Hospital, New York in 1941, aged 72, and was buried in the Beth Olom Cemetery in Queens. He was survived by his wife and his sister, Lotta. On May 6, 2008, Dr. Lasker was among the first 40 German sportsmen to be elected into the "Hall of Fame des Deutschen Sports".

******

"It is not possible to learn much from him. One can only stand and wonder." - <Max Euwe> Euwe lost all three of his games against Lasker, the most lopsided result between any two world champions.

"My chess hero" - <Viktor Korchnoi>

"The greatest of the champions was, of course, Emanuel Lasker" - <Mikhail Tal>

"Lies and hypocrisy do not survive for long on the chessboard. The creative combination lies bare the presumption of a lie, while the merciless fact, culminating in a checkmate, contradicts the hypocrite." – <Emanuel Lasker>

"Lasker, a natural genius, who developed thanks to very hard work in the early period of his career, never adhered to the type of play that could be classified as a definite style." None of the great players has been so incomprehensible to the majority of amateurs and even masters, as Lasker."- Capablanca

"Lasker was my teacher, and without him I could not have become whom I became. The idea of chess art is unthinkable without Emmanuel Lasker."- Alekhine

Lasker is one of the main inspirations to write this blog. Along with Zukertort, Schlechter, Rubinstein and Chigorin, his ability to showcase the virtues of Black's position after 1.e4 e5 is almost inexhaustible. Extreme solidity, a forceful dynamism and deep positional and tactical richness govern his play. Let us look at some examples of how Lasker handles open games:

The following game is against David Janowski, a brilliant player who had the misfortune of facing Lasker and Capablanca in his career....

David Janowski

(1868-1927)

In the following game, played in Paris, 1900, Lasker shows the strength of his hand. His moves have a powerful conviction behind them, as if the result of the game was predestined....