Ruy López: Jaenisch Gambit | TRIPPING at the finish line! 🫠

#ruylopez #jaenischgambit #blunder #brilliancy #rooksacrifice

A proposition:

Conceptualising the endpoint of chess in a trinary fashion, only in terms of a win, loss, and draw, fails to capture the romance of chess!

— vitualis the Chess Noob

Sure, it’s good to win, but I will claim that winning with style is qualitatively superior! When we turn our minds to the DRAW, a tie, it is commonly but wrongly seen as a boring outcome. Now, some draws are indeed boring, for instance, the Berlin Defense draw in the Ruy López Opening. However, one of the most elating experiences in chess is wrangling a draw, for instance, by stalemate or threefold repetition, in an otherwise completely lost position.

This is not one of those games, at least, not for me! This game is a sad tale where I was forced to accept a draw in a completely won position, after having navigated a difficult endgame under severe time pressure; snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, tripping at the finish line, in other words, an epic fail! 😂

I had the black pieces and the game proceeds down a typical Jaenisch Gambit against White’s Ruy López Opening (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 f5).

![]()

A historical note:

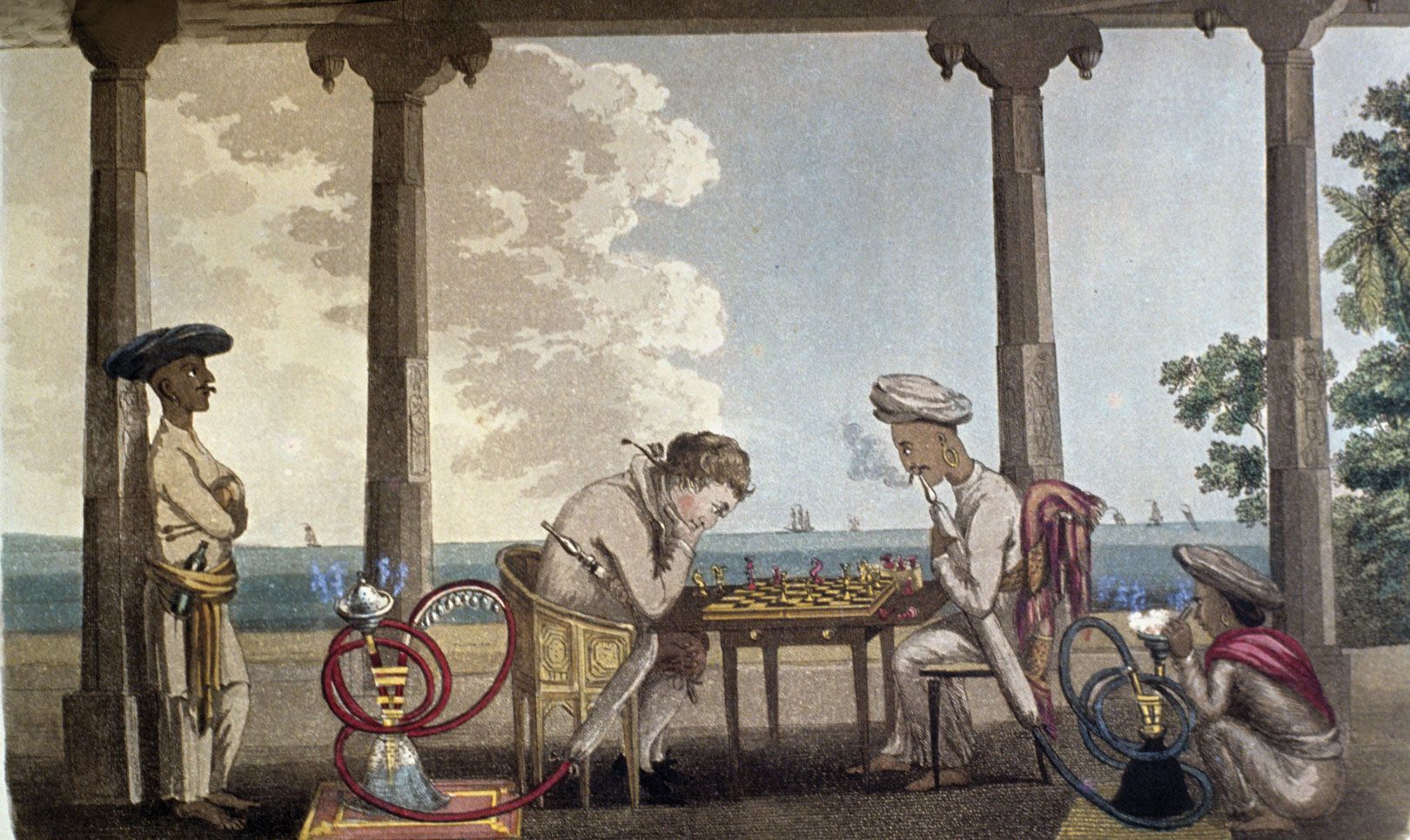

The earliest game of the Jaenisch Gambit in the massive and free LubrasGigabase of over 13.2 million chess games was played by John Cochrane (1798-1878) against Moheschunder Bannerjee in the city of Kolkata (Calcutta), India.

Cochrane was a renown Scottish chess master (Howard Staunton was his protégé!) and a barrister in Calcutta, then the de facto capital of British-rule in India. Bannerjee was a Brahmin in a local village with a fearsome reputation that he had never been beaten locally, and was invited to the Calcutta Chess Club in 1850 to play against Cochrane in a series historical games. Bannerjee’s very solid approach to several openings common in Indian chess is source of names including the “Indian Game”, and the various King’s/Queen’s “Indian Attack/Defense”. In the West, it wasn’t until the emergence of the Hypermodern School and chess masters like Tartakower in the 1920s that these Indian openings became popularly known.

The Jaenisch Gambit itself was developed by Finnish-Russian chess master Carl Jaenisch only a few years earlier in 1847, and was understood as an aggressive response to the Ruy López Opening in the romantic tradition. There are games of the Jaenisch Gambit played by many of the strongest chess players of the era, including Steinitz, Bird, Blackburne, Lasker, Tarrasch, and Marshall.

![]()

Now, where (Bannerjee — Cochrane, 1850 Calcutta, India) went down the Exchange Variation, my opponent with the white pieces who coincidentally was also from India, opted to play in a cautious and relatively closed approach. However, one of the advantages of the Jaenisch Gambit is that ostensibly sensible looking moves for White are inaccurate, e.g., developing the rook to control the e-file (7. Re1?!) and choosing to not exchange the Ruy López bishop when challenged (9… a6 10. Ba4). By this position, I had accrued a decent advantage of [-1] according to the engine by the early middlegame.

On move 16, White makes a bold move (16. Qd5?), lining up their bishop and queen in a battery. Stockfish doesn’t approve of this tactic and rates it a mistake [-4.5], though I needed to counter it. I don’t find the immediate best response to punish White, the bishop sacrifice (16… Bxh3), punching a hole in White’s king’s defences, but do find the next best move by sacrificing… the ROOK (17… Rxf3!!). My follow-through, however, was critically flawed (19… Bxh3+??) with the evaluation flipping from [-2.6 → +3.1]! White’s king managed to escape back to the e-file and was well defended by a bunker of pawns on the f- and e-files.

My poorly considered (19… Bxh3+??) also resulted in a hung c6-knight, which was also pinned to my a8-rook. Salvaging the situation was necessary, but my initiative was lost. Luckily for me, the position was complex and White must have taken the view that they could consolidate their nominal single point of material advantage by simplifying and trading down pieces. They offered/forced a queen trade (23. Qf7?), and this actually brought the evaluation back to equality [0.00]!

A few more trades later, and the dust settles on move 26, and we see the potential problem White faced. White had the rook pair and a bishop, while I had the bishop pair and a rook. I’ve noted in a previous video that when there are a lot of pawns left on the board, and there were, a bishop pair can often be relatively better than a rook pair. Although White was up a point of material, the engine evaluation was equal. In practice, this means that Black has some form of compensation. In this game, this was in the form of better mobility of the pieces (the bishops in a crowded board), which usually means that it’s easier to play!

We see this in the next 10 moves. White’s rooks have difficulty making progress or forming an attack. On the other hand, my bishop pair creates an attacking idea with my pawn advances. Moreover, my numerical pawn superiority, along with White’s doubled f-pawns, create difficult threats that White must counter. White attempted to bring the king into the attack, a good endgame tactic. However, I saw a potential trap – simply, it was too soon for White’s king and my control of the dark squares meant that I could predict what White was going to try. They were going to try infiltrating their king along the light squares. I baited them to moving their king forward again with (32… c5!?), a tricky move in the context that if White was committed to their plan, they may have tunnel vision!

And yes, (34. Kc4??), a blunder! With (34… Be6+), I skewered White’s king against their bishop. My control of the dark squares mean that the white king could not escape check and defend their bishop, allowing me to win their bishop cleanly!

However, I only 1 ½ minutes left on the clock to my opponent’s 11 minutes. I need to play carefully, but swiftly to consolidate the advantage. Optimally, I needed to simplify – perhaps forcing a trade of one of my bishops for one of White’s rooks and pushing forward to promote a pawn. All the while, I had to keep my king safe!

On move 45, I managed to play (45… Kh6), bunkering my king into a very safe nook of two pawns. Yes! I could now put my focus elsewhere. My most valuable piece was the a-pawn, an outside passed pawn. Black still had a passed e-pawn that I needed to keep an eye on. I had just under a minute left now!

On move 48, White makes a mistake with (48. e5), which loses their e-pawn. However, is it really a mistake? For White, their goal is to play quickly so that I can’t think on their time. Using time against me would be their best approach! I find a tricky and difficult move for White to navigate with (48… Bxe5), and White spends three minutes on the next move, giving me some respite to calculate options. And I could see it: push the a-pawn to promotion, which would force White to trade a rook for my dark square bishop and pawn. Then, with my remaining bishop and rook, I should be able to easily to promote my h-pawn, or force White to trade away their final rook. I felt confident that with my 15 second increment, I shouldn’t run out of time!

It goes to plan: (52… a1=Q 53. Rxa1 Bxa1 54. Rxa1), and it’s a completely winning endgame where I have an extra piece and a pawn majority. In the following moves, my clock starts to go up with each move. And there lies the hazard! It is most dangerous when you feel that the danger is over! On move 60, I stumble, trip, and faceplant at the finish line with (60… Bf3??), a ridiculous blunder of the bishop [-M19 → 0.00]! I realised that I’d blundered almost immediately as my finger let go of the mouse button!

I recognised that the game had entered a draw [0.00], so it was important to not make another mistake, or potentially lose on time! White has the advantage as they are not under time pressure. So, there was an imperative to force a draw before White realises that they can potentially stall the game with tricky attacks to try to get a win! I invite a trade of rooks, and it is done. A draw due to insufficient material, GG!

The big takeaway from this game is the principle, “never give up, never surrender”! If you keep making attacks, even in a losing position, it sometimes creates the setting where your opponent will make a blunder!