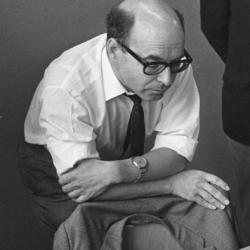

GM David Bronstein

Bio

Early Life And Career

David Bronstein was born in Bila Tserkva, just outside of Kyiv, in present-day Ukraine in 1924. He learned chess at the age of six. Within a decade, he was one of the top Ukrainian players as a teenager, placing second at the 1940 Ukrainian Chess Championship behind Isaac Boleslavsky. The performance earned him the Soviet Master title.

Because of World War II, it was not until 1944 when Bronstein could play in a Soviet Championship. Although he placed just 15th in a field of 17, he won his game against tournament winner Mikhail Botvinnik. It was the first time that the two met over a chessboard but would not be the last.

In the 1945 Soviet Championship, Bronstein improved dramatically and finished in third place. In 1948 and 1949, he tied for first. In the meantime, he won the 1948 Interzonal tournament in Sweden to advance to the 1950 Candidates tournament for the world championship.

1951 World Championship

Bronstein came a draw away from becoming world champion in 1951.

At the 1950 Candidates, he entered the final round a half-point behind Boleslavsky, who made a quick draw. Bronstein’s win (below) over Paul Keres forced a 12-game playoff for the right to be Botvinnik’s first challenger as world champion.

After those 12 games, Bronstein and Boleslavsky remained even after two wins apiece, sending the playoff into sudden death. Game 13 was drawn. Then in the 14th game, Bronstein as Black used the Winawer French to defeat Boleslavsky in just 29 moves. At the age of just 27, Bronstein was one step away from the world championship.

Bronstein had made it to the match with Botvinnik after drawing both the round-robin Candidates and the 12 initial playoff games. However, a drawn match at the world championship would not result in a playoff; instead, Botvinnik would retain the title.

Bronstein struck first with a victory in game 5 (below) but dropped the next two games, including an endgame blunder in game 6. Bronstein evened the match with a win game 11 but once again lost the next game. With the match half complete, he was behind at +2 -3 =7.

The seesaw battle continued in the second half: Bronstein won game 17 but then lost the 19th game and again trailed in the match. However, with consecutive wins in the 21st and 22nd games, Bronstein took the lead in the match and needed only an even split in the last two games to become world champion. Particularly impressive was his game-22 victory over Botvinnik’s Dutch Defense.

In keeping with his pattern throughout the match, however, Bronstein lost the next game. He now needed a win in the final game, but a 22-move draw allowed Botvinnik to retain the world championship.

The 1950 Candidates and 1951 Championship have been the subject of much speculation regarding fixed games and outcomes—none of them proven. Bronstein claimed later that he was not interested in becoming the world champion and did not want to deal with the bureaucratic duties that would accompany the position.

Regardless of what may have occurred behind the scenes, Bronstein missed out on the world championship of chess by only the narrowest possible margin.

After The Match

Bronstein played in the next two Candidates tournaments in 1953 and 1956 (automatically qualifying for the former and reaching the latter via a 1955 Interzonal victory), but Vassily Smyslov won them both. Bronstein finished tied for second in 1953 and tied for third in 1956, both times finishing two points behind Smyslov.

Still only 32 years old at the time of the 1956 Candidates, Bronstein never made it so far in the cycle again. He finished a half-point outside the Candidates qualifiers at the 1958 Interzonal, and he didn’t play in 1961.

At the 1964 Interzonal in Amsterdam, Bronstein finished sixth, a standing that qualified for the 1965 Candidates. However, he had just the fifth best result among Soviet players, and FIDE rules limited each nation to a maximum of three qualifiers. As a result, Bronstein failed to advance.

The 1964 Interzonal was Bronstein’s last until 1973 at Petropolis in Greece, where he may have played the best game of his career, sacrificing a rook and an exchange to beat Ljubomir Ljubojevic.

Despite that victory and a plus score overall (+7 -3 =7), Bronstein finished sixth. Just the top three players qualified for the Candidates. It was his final Interzonal.

Bronstein remained an active player well into the 1990s except for a break in the mid-1980s that may have been due to politics. He always maintained an independent mind and refused to sign a letter denouncing Viktor Korchnoi’s 1976 defection from the Soviet Union. Bronstein lost his state stipend, and his ability to compete outside of the country was severely curtailed.

Contributions To Chess

Bronstein was at the forefront of chess openings, literature, and time controls.

Bronstein’s name is closely associated with at least three openings: King’s Gambit, King’s Indian Defense, and Caro-Kann. He used the King’s Gambit to great effect, including playing it in three games that he won during the 1945 USSR Championship. He is often credited with reviving the King’s Indian as a legitimate response to 1. d4. And a somewhat popular variation of the Caro-Kann is named for Bronstein and Bent Larsen (1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Nf6 5. Nxf6 gxf6).

Bronstein wrote several chess books. Most notably, his review of the 1953 Candidates tournament in Zurich was published in 1956 and translated into English in 1979. It is considered one of the best tournament books ever written. Other highlights include the part-autobiography, part-game collection The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, co-written with Tom Furstenberg and published in 1995. Bronstein’s connection to the King’s Indian Defense was bolstered with a 1999 treatise on the opening. He also wrote a longtime chess column for the newspaper Izvestia.

Bronstein also invented the popular time control that bears his name, and his exploits against computers were also notable, as he played recorded games against them as far back as 1963.

Legacy

Bronstein’s name arises whenever the subject of “the best player never to become world champion” arises. Spending nearly 30 years (roughly 1945-1975) as a top player and coming so close to winning the world championship, he certainly has a strong case.

However, Bronstein’s legacy goes far beyond his near-miss in the 1951 world championship match. His creativity as an attacker, his opening exploits, his writings, and his independent streak all leave a lasting impression.